Exhibition place:Textile Conservation Gallery, China National Silk Museum

Exhibition time:2019.5 - 2019.8

Preface

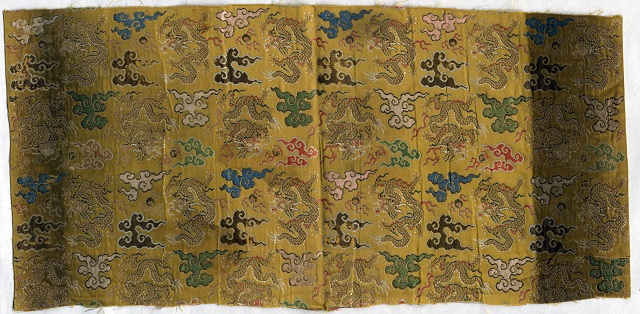

Chinoiserie Brocade

No. 2016.18.24

France, 191cmx72cm

Dyestuffs: Kermes(red) and lac(crimson)

The Kermes (kermes vermilio) grows on kermes oak (Quercus coccifera) and originates from the Mediterranean, including France, Spain, Morocco, Turkey and Lebanon. The main component of the scale insect dye is kermesic acid. Another branch of the Coccidea family that people are more familiar with is Dactylopius spp., indigenous to Central and South America. At present, there are still some villagers in Peru and Mexico feeding such insects living in cactus of the Opuntia family. This product consists predominately of carminic acid.

Due to prosperous overseas trade, England and Holland were developed into both important financial centers and European centers of the dyeing industry in the 16th century. After Louis XIV ascended the throne, his chief minister dedicated to developing economy. The textile industry was given a priority and issued regulations stipulated that dyeing wool must use some certain of dyes.

Brocade with Lace Design

No.2016.18.31

Holland, 94cmx39cm

Dyestuffs: Sappanwood(red), safflower(red), weld(yellow) and indigo(blue)

Weld (Reseda luteola), wild but also cultivated, grows in Southwestern Europe, the Mediterranean and North Africa. It was the most-used yellow dye from the 17th to 20th century, with main components of luteolin, apigenin and relative glucosides.

For Europe, both sappanwood (Caesalpinia sappan) and safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) were the exotic plant dyes. The former is native to Southeast Asia and the latter probably Egypt. Dyeing with alum, sappanwood can produce wood red. The dyeing process of safflower is highly complicated and little carthamin can be obtained after removing yellow pigments. However, the pure and bright hue of carthamin was so charming that dyers of Europe and Asia could not help falling in love with it. As a result, it had been widely used to color red with various shades from the beginning of the 17th century to the end of the 19th century. There are two kinds of maritime creatures used as natural dyes, molluscs and lichens. With complicated dyeing process and high costs, different shades of purple can be obtained from molluscus. Lichens, fungus organisms growing in rocky cliffs of the Mediterranean and the Atlantic coast, can be used to produce orchil or archil dyes they were obtained. The record of dyeing with lichens can be dated back to 2,000 years ago. Using lichens, blue purple will be produced amid alkaline conditions, while red purple be obtained within acidic conditions.

As 18th century was an age of scientific exploration, chemists and dyers had great interests in dye science which included in Newton's Color Theory. At the same period, people had an even larger demand of colors after the invention of the Spinning Jenny. Indigo carmine, as the first semi-synthetic dye came out in 1740, later synthetic aluminum sulfate took the place of alum. One hundred years after that, the invention of mauveine ended up the market of natural dyes.

Part 2 Asian traditions

Although there are many countries in Europe, the types of their dyestuffs are similar. Whilst dyestuffs in Asia have unique and distinctive features vary with areas.

Iran’s dyestuffs represented Central Asian dyestuffs and its carpet is a world famous specialty. And the rise and fall of the carpet industry also indicated the development of dyes. The Safavid Dynasty (Mid-16th to Mid-18th centuries) was an era of carpet-weaving when Iran was ruled by Persians. Dyes of high quality are required for fine patterns and brilliant colors. Subsequently, records on carpets are even less due to the war. It was not until the late 18th century, with the establishment of the Qājār Dynasty, that the carpet industry was gradually restored. For 300 years, Iranian dyers have been using madder as red dye, larkspur as yellow dye, pomegranate peels and sumac galls as black dyes, Lac and indigo (Indigofera tinctoria) from India were also used for dyeing Iranian textiles.

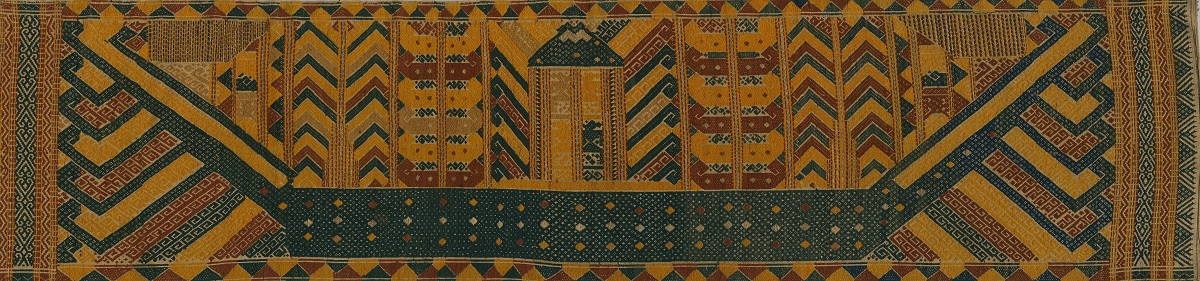

Ceremonial Boat Cloth

No.2014.61.15

Indonesia, 232cmx56cm

Dyestuffs: Indian mulberry(red), turmeric(yellow) and indigo (blue)

Larkspur (Delphinium semibarbatum), which is used for making yellow dyestuff is unique in Iran, Afghanistan and north India. There are few historical records about it. The Kesi robe dyed with larkspur in the Uighur period was unearthed in Xinjiang, China.

Indian mulberry (Morinda citrifolia) is a typical red dyestuff in southeast Asia. Its main component is an anthraquinone compound, morinone. In the 17th and 19th centuries, Turmeric (Curcuma longa) was the most widely used yellow dyestuff in Southeast Asia, Indochina and Southern China. The dyestuff is easy to tint but has low light fastness. The main components are curcumin and its two derivatives.

Embroidered Crane Roundels

No.0302

China, 30cmx22cm

Dyestuffs: Sapanwood(red), indigo(blue), amur cork(yellow), turmeric(yellow) and Huangjing (Vitex negundo)(yellow)

Tannin and Indigo

Tannin-type dyes were mainly used to produce blacks on textiles all over the world in the past, for example, various species of oak trees (Quercus spp) have been widely applied to dyeing and producing black with iron from the 17th century to the end of 19th century. In addition to oak, European and Asian dyers dyed black with sumac, not only barks and leaves (e.g. Rhus coriaria) but also galls (e.g. Rhus chinensis) of these plants contain abundant of tannin. In Central Asia, the dyers would use local specialties such as pomegranate (Punica granatum) and walnut (Juglans regia) to produce black. It is quite difficult to identify plant sources of the black dyes as most of them contain mainly tannins and they would form ellagic acid after adsorbing on fabric fibers in most cases. The similar problem also arises when distinguish the different species of indigo-based plants, such as Isatis tinctoria (Europe), Polygonum tinctorium (East Asia), Indigofera tinctoria (Southeast Asia) and strobilanthes cusia (South Asia) as extracts of all indigo dyed textiles have indigotin and indirubin as the major components. Among these four plants, Indigofera tinctoria and strobilanthes cusia contain high content of indigoids, so they were widely used after the 18th century. Therefore, India became the largest exporter of indigo in the world during the 17th century to the early 20th century. Pay attention to us

×

Pay attention to us

×