Exhibition place:Fashion Gallery

Exhibition time:2018.5 - 2018.9

According to Joseph Needham, the character“机” (ji) in ancient Chinese has double meanings: (1) Loom; (2) Matter of wit and intelligence. These definitions equate loom with the ability to learn and invent. People from all corners of the world share the knowledge of loom and weaving. However, as this exhibit attests, different regions in different periods develop specific looms to produce unique textile types.

A World of Looms is organized by the China National Silk Museum with the support of many scholars and research institutions. It is the first exhibition in China to present the rich cultural heritage of looms and weaving technologies from around the world. The displays include more than 50 looms and many of their associated textiles, organized by their geographical locations. These objects celebrate the marches of textile innovations through the lens of global textile traditions: It highlights the vital role of cultural exchanges along the Silk Road for the evolution of loom types in China and its bordering regions. Furthermore, it illustrates the adaptions of looms and weaving practice worldwide in facing the rapid change of traditional custom and in meeting new demands. Last, it emphasizes the need to preserve weaving knowledge, for it is quintessential to all cultures. (Zhao Feng)

1. CHINA

China has a long and rich history related to weaving and loom. Preliminary loom has been developed more than 7000 years ago. The Warring States and Han Dynasty (5th century BCE – 2nd century CE) saw the evolution of treadle and multi-heddle looms. This is also the time when weaving technology reached its historical peak. Through the cultural exchanges on the Silk Roads, drawloom was developed; it achieved its final form before the Tang Dynasty (7th–9th century) and became the dominant system for weaving patterned silks from the Song Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty (10th–19th century). On the UNESCO list, the cultural heritages preserved from the China past include both the tangible and the intangible. Among these are the excavated pattern loom models from the Han Dynasty as well as the Sericulture and Silk Craftsmanship of China, which include the weaving and loom of both the Han and the Minority Groups. (Zhao Feng)

1.1 Early Looms

Early looms in China are mostly simple backstrap looms, where the warp is stretched between some stationary objects and the body of the weaver. The foundation weave is generally plain weave. The two plain weave sheds are called natural shed and counter shed. The first is operated by means of a shed roll over which one set of warp pass, and the second by a continuous string heddle which encase individual thread of the other set of warp. Weavers lean back and forth, using their body weight to adjust tension of the warp. As they lean forward, the tension is relaxed and they can raise the string heddle to open one shed. As they lean back, the warp is stretched and turns to its natural shed with the shed roller. The weavers can then draw the shed roll towards them to widen the shed. (Long Bo)

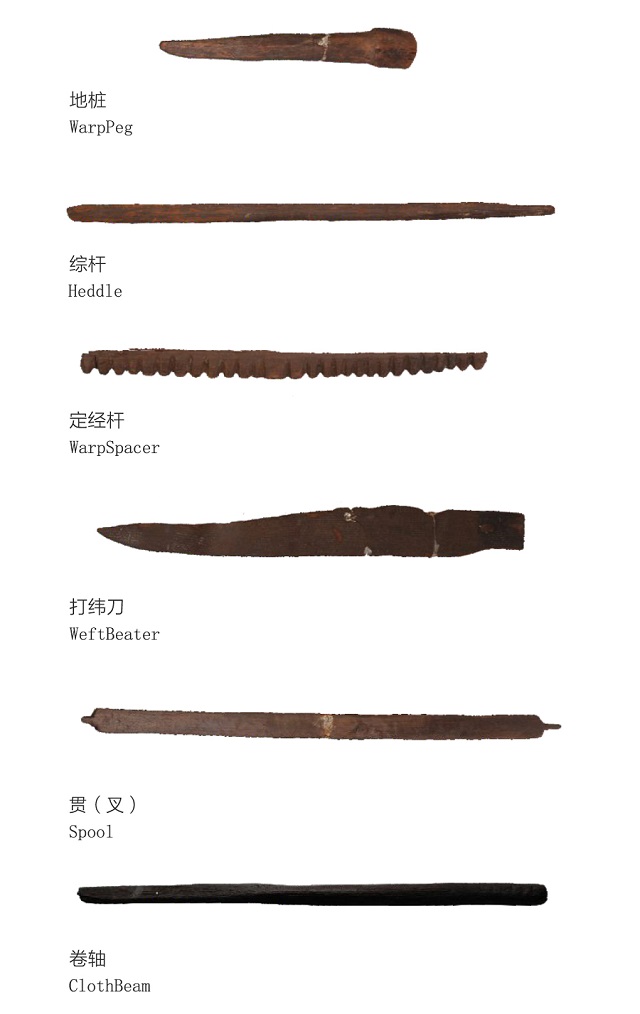

Tianluoshan Loom Dated to 6,500 years ago, wooden

Excavated from Yuyao, Zhejiang Province

Collection of Zhejiang Institute of Archaeology

The Tianluoshan site is located in Yuyao City, and belongs to the ancient Hemudu culture. The loom parts excavated from the Tianluoshan site come from simple backstrap looms. In such loom, one end of the warp would be tied to a warp beam. In the middle, there would be a heddle rod and a weft beater. The other end of the warp is connected to a cloth beam, which is strapped to the waist of the weaver. (Long Bo)

Liangzhu Jade Loom Jade

Unearthed from Liangzhu, Zhejiang Province

Collection of Liangzhu Museum

Loom parts made of jade were excavated at the Liangzhu Cultural Cemetery in Yuhang District, Hangzhou in 1986. Three pairs of six end-pieces of loom parts were found in symmetrical alignments, each pair were placed 35 cm apart. The gaps must indicate the now-missing wooden rods that have deteriorated over time. These end-pieces are enough evidence to visually construct a simple backstrap loom. (Long Bo)

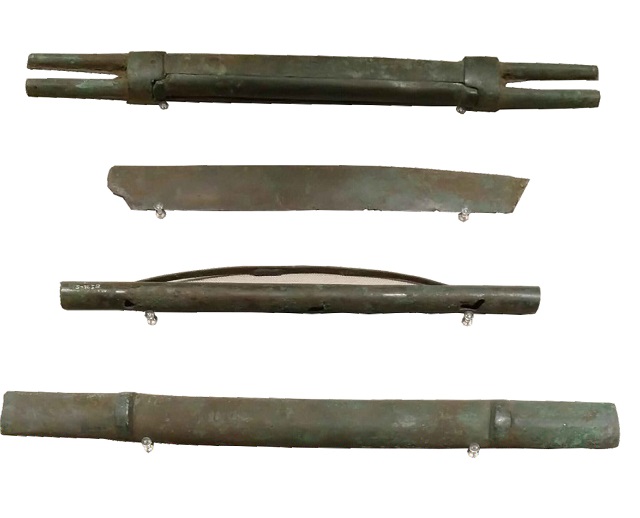

Shizhaishan Bronze Loom

Bronze Excavated from Jinning, Yunnan Province

Collection of Yunnan Museum

Four loom parts made of bronze were excavated from the Shizhaishan site, Jinning, Yunnan Province. They consist of a warp beam, a heddle rod, a weft beater, and a cloth beam. Together they form a simple backstrap loom. This site and the Lijiashan site in Jiangchuan have also yielded two bronze cowrie containers that depict a scene of a textile workshop. Both sites are dated to the Western Han Dynasty (206 BCE–8 CE). (Long Bo)

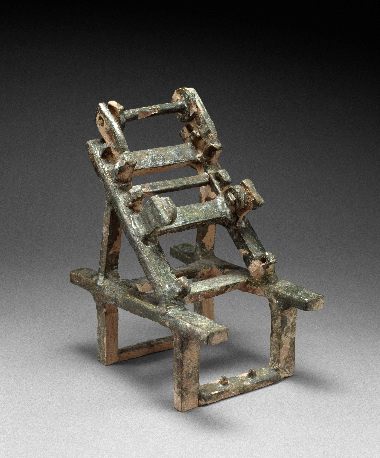

Laoguanshan Pattern Loom

Four models of hook-shaft pattern loom were excavated in 2012 inside the Laoguanshan Han Dynasty tomb in Chengdu, Sichuan Province. They were constructed of wood and bamboo and discovered at the bottom of a wooden coffin, along with remnants of silk threads and dyes. The largest of the four looms measures H. 50 x L.70 x W. 20 cm. The other three are smaller, around H.45 x L.60 x W.15 cm. Of equal interest, there were 15 painted wooden figurines, which—as indicated by their postures and accompanying inscriptions—may be representations of workers at a weaving workshop where Sichuan jin silks were produced. To date, these miniature looms are the only complete loom models from the Han dynasty that bear a confirmed provenance. (Long Bo)

1.2. Treadle Looms

Treadle loom is a generic term for a loom equipped with a pedal that is used to lift a shed opening device. The use of pedal changed the simple shedding system operated by hand to the treadle-lifting shedding system operated by feet. The new system free up the hands from picking up and beating the wefts and greatly improved the efficiency of weaving. Treadle loom first appeared in China during the Spring and Autumn and the Warring States Dynasties. The first visual depiction of the loom, however, is found in the Eastern Han Dynasty. There are several types of pedal loom with different number combination of heddles and treadles. (Long Bo)

Ceramic Loom Model (3D Print)

H.30 cm x L.25 cm x W.17 cm Han Dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE)

The original is in the collection of the Musée Guimet

A loom model of green-glazed ceramic, dated to the Han Dynasty, was collected by Mrs. Riboud, a well-known Chinese textile history expert. Although it has no exact excavation provenance, this object is a very important material in the study of Han Dynasty looms. The form of the loom conforms to the oblique treadle looms depicted on numerous stone relief carvings from the Han Dynasty. (Long Bo)

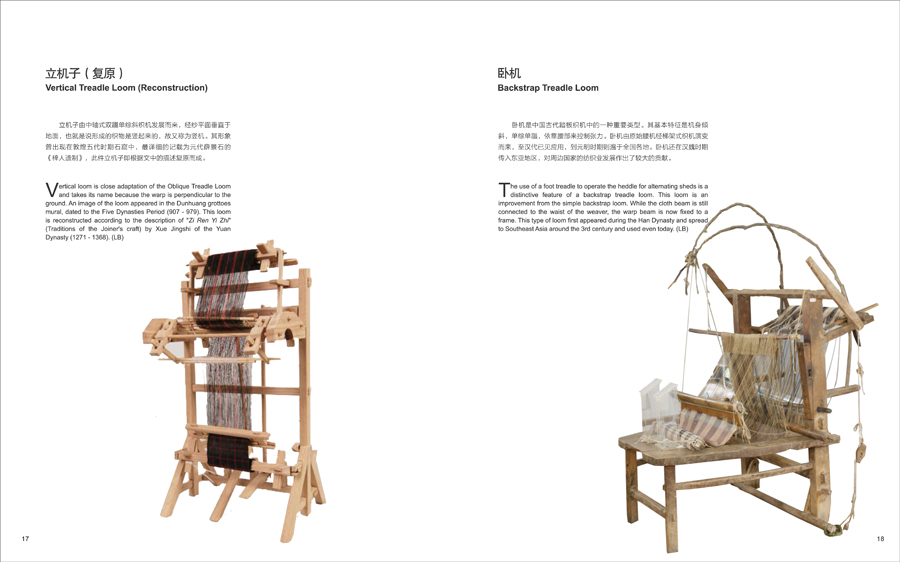

Vertical Treadle Loom (Reconstruction)

Vertical loom is close adaptation of the Oblique Treadle Loom and takes its name because the warp is perpendicular to the ground. An image of the loom appeared in the Dunhuang grottoes mural, dated to the Five Dynasties Period. This loom is reconstructed according to the description of "Zi Ren Yi Zhi" (Traditions of the Joiner’s craft) by Xue Jing Shi of the Yuan Dynasty. (Long Bo)

Backstrap Treadle Loom

The use of a foot treadle to operate the heddle for alternating sheds is a distinctive feature of a backstrap treadle loom. This loom an improvement from the simple backstrap loom. While the cloth beam is still connected to the waist of the weaver, the warp beam is now fixed to a frame. This type of loom first appeared during the Han Dynasty and spread to Southeast Asia around the 3rd century. (Long Bo)

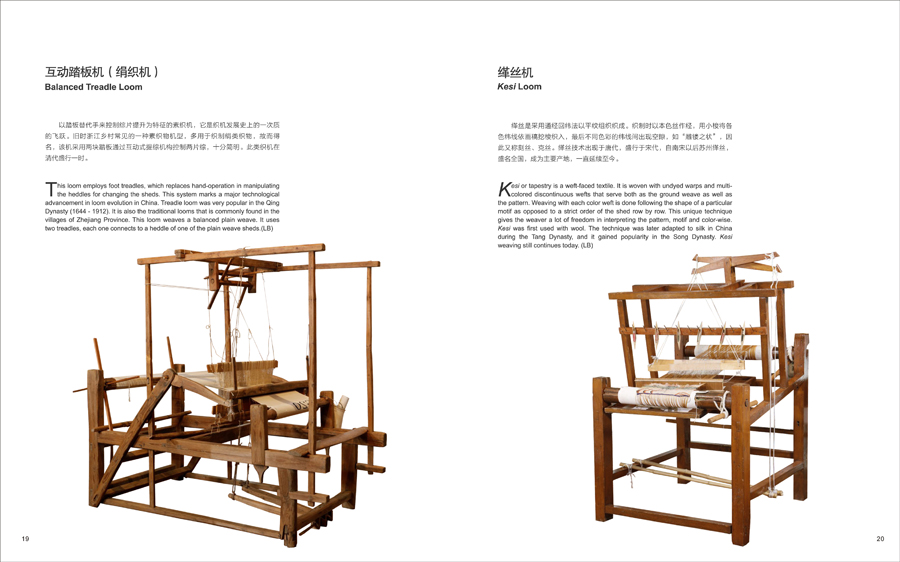

Balanced Treadle Loom

This loom employs foot treadles, which replaces hand-operation in manipulating the heddles for changing the sheds. This system marks a major technological advancement in loom evolution in China. Treadle loom was very popular in the Qing Dynasty. It is also the traditional looms that is commonly found in the villages of Zhejiang Province. This loom weaves a balanced plain weave. It uses two treadles, each one connects to a heddle of one of the plain weave sheds. (Long Bo)

Kesi Loom

Kesi or tapestry is a weft-faced textile. It is woven with undyed warps and multi-colored discontinuous wefts that serve both as the ground weave as well as the pattern. Weaving with each color weft is done following the shape of a particular motif as opposed to a strict order of the shed row by row. This unique technique gives the weaver a lot of freedom in interpreting the pattern, motif and color-wise. Kesi was first used with wool. The technique was later adapted to silk in China during the Tang Dynasty, and it gained popularity in the Song Dynasty. Kesi weaving still continues today. (Long Bo)

1.3 Pattern Looms

Large and complicated patterns require a more sophisticated patterning system that allows repetition of some actions at regular intervals. In other words, the loom needs a system that allows both the storage and easy retrieval of the pattern. This need was answered by the heddles and shafts system, which led to the development of multi-shafts patterning looms and the drawloom. (Long Bo)

Taiwan Atayal Loom

This is a unique type of backstrap loom used by some aboriginal groups in Taiwan. The cloth beam is secured at the weaver’s waist, while the large, hollow warp beam (on the right in the photograph) rests behind the weaver’s feet. To adjust the tension in the warp the weaver flexes the warp beam with her feet. Fibers for weaving include hemp, ramie, cotton and hibiscus. Stripe patterns and small geometric designs are made using various aids, including heddles and sticks embedded in the warp. Weaving on this type of loom had become rare, but recently there has been a revival of interest in traditional weaving in Taiwan. (Long Bo)

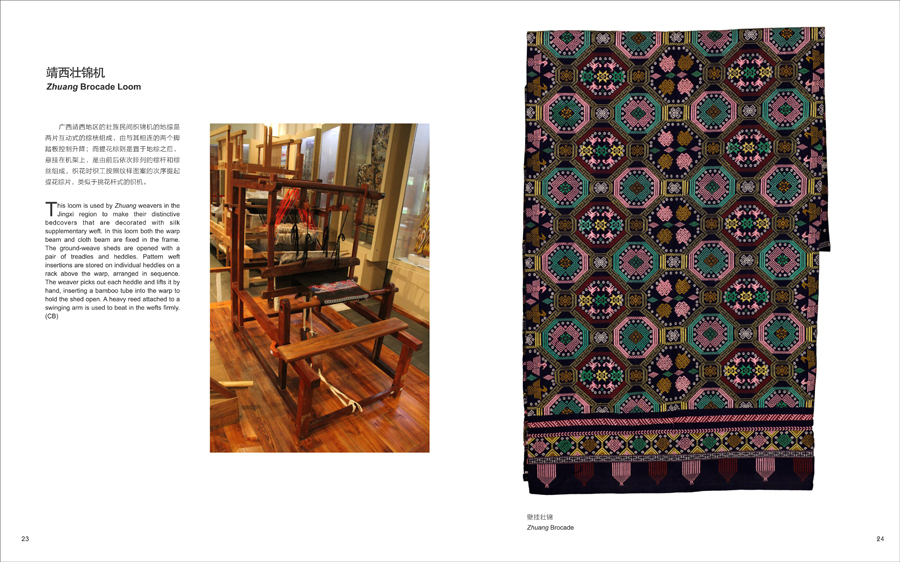

Zhuang Brocade Loom

This loom is used by Zhuang weavers in the Jingxi region to make their distinctive bedcovers that are decorated with silk supplementary weft. In this loom both the warp beam and cloth beam are fixed in the frame. The ground-weave sheds are opened with a pair of treadles and heddles. Pattern weft insertions are stored on individual heddles on a rack above the warp, arranged in sequence. The weaver picks out each heddle and lifts it by hand, inserting a bamboo tube into the warp to hold the shed open. A heavy reed attached to a swinging arm is used to beat in the wefts firmly. (Long Bo)

Wang Hanging of Zhuang Brocade

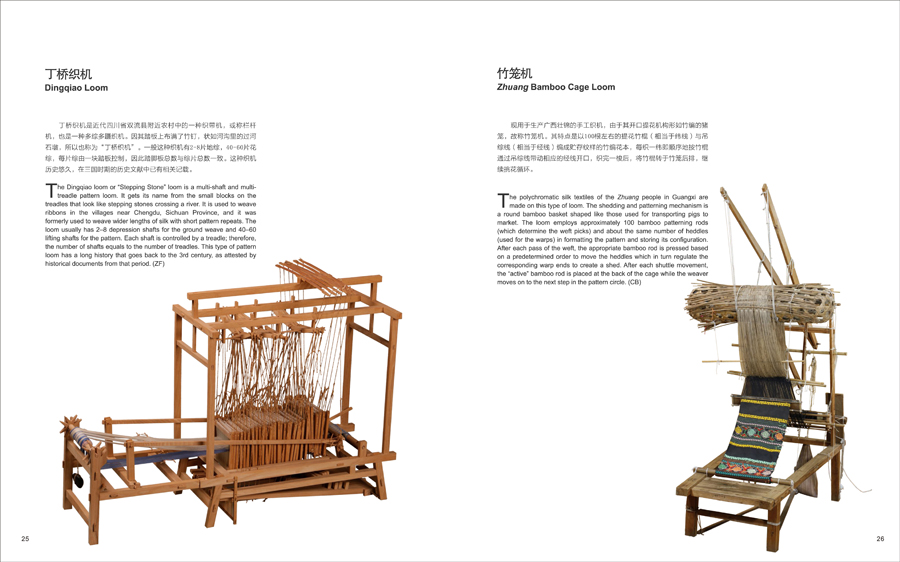

Dingqiao Loom

The Dingqiao loom or “Stepping Stone” loom is a multi-shaft and multi-treadle pattern loom. It gets its name from the small blocks on the treadles that look like stepping stones crossing a river. It is used to weave ribbons in the villages near Chengdu, Sichuan Province, and it was formerly used to weave wider lengths of silk with short pattern repeats. The loom usually has 2–8 depression shafts for the ground weave and 40–60 lifting shafts for the pattern. Each shaft is controlled by a treadle; therefore, the number of shafts equals to the number of treadles. This type of pattern loom has a long history that goes back to the 3rd century, as attested by historical documents from that period. (Long Bo)

Zhuang Bamboo Cage Loom

The polychromatic silk textiles of the Zhuang people in Guangxi are made on this type of loom. The shedding and patterning mechanism is a round bamboo basket shaped like those used for transporting pigs to market. The loom employs approximately 100 bamboo patterning rods (which determine the weft picks) and about the same number of heddles (used for the warps) in formatting the pattern and storing its configuration. After each pass of the weft, the appropriate bamboo rod is pressed based on a predetermined order to move the heddles which in turn regulate the corresponding warp ends to create a shed. After each shuttle movement, the “active” bamboo rod is placed at the back of the cage while the weaver moves on to the next step in the pattern circle. (Long Bo)

Dai Brocade Loom

This distinctive loom is used by Dai weavers in the Jinghong region of Yunnan Province. The cloth beam is attached to the weaver’s waist, and the warp beam is lodged in the loom frame. There are two treadles: depressing one raises the heddle that opens the ground weave shed, while depressing the other raises the pattern harness. Patterns are stored on loop threads or sticks in a pattern harness that stretches above and below the loom: each loop records one pattern weft insertion. After each pass of the weft, the ‘active’ loop, is transferred from the top of the pattern harness to the underneath part. A loom may have as many as 100 looped threads. Similar patterning systems are used by Tai weavers in Vietnam, Laos and Thailand, though the looms used by these weavers are fundamentally different. (Long Bo)

Dai Brocade with Peacock and Elephant Pattern

Dong (Kam) Brocade Loom

Commonly known as “Douji,” this loom is unique to the Dong people living in the Tongdao area of Hunan and parts of nearby Guizhou Province. They use it to weave cloth decorated with supplementary weft, for use on baby carriers and wedding bedcovers. The warp beam is fixed in the loom, and the cloth beam is attached to the weaver’s waist. The weaver has two loops of cord around her feet: pulling one raises the ground-weave heddle, while pulling the other raises the pattern heddle. Pattern weft insertions are stored on sticks above the warp, in a system that is similar to the brocade loom used by Dai weavers in Yunnan Province. The ground-weave is usually cotton, while the colorful wefts can be either cotton or silk. (Long Bo)

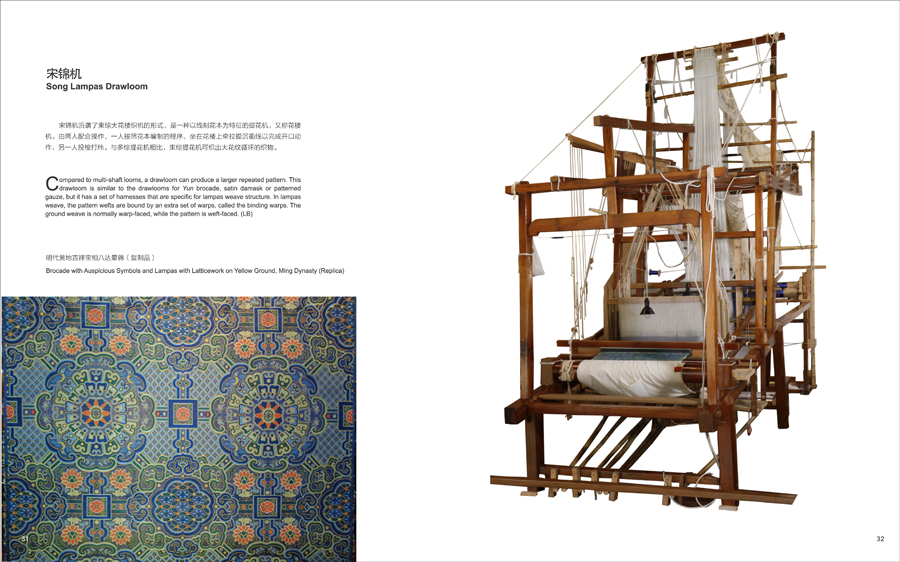

Song Lampas Drawloom

Compared to multi-shaft looms, a drawloom can produce a larger repeated pattern. This drawloom is similar to the drawlooms for Yun brocade, satin damask or patterned gauze, but it has a set of harnesses that are specific for lampas weave structure. In lampas weave, the pattern wefts are bound by an extra set of warps, called the binding warps. The ground weave is normally warp-faced, while the pattern is weft-faced. (Long Bo)

Brocade with Auspicious Symbols and Lampas with Latticework on Yellow Ground, Ming Dynasty (Replica)

Gauze Loom

This sophisticated loom is a special type of drawloom used for making Hangzhou gauze. The gauze structure is made by a combination of standard harnesses and special doup harnesses that raise alternate warps, moving them to one side and back again, creating twists in the warp, through which the weft is inserted. The twists allow the weaver to create a stable weave that has large openings in it, making a light and cool fabric. The loom has a pattern-tower controlled by an assistant (drawperson), which adds damask-like repeating patterns to the finished textile. (Long Bo)

Damask Loom

This loom belongs to a type of drawloom called the Lesser or Horizontal Drawloom. It is mainly suitable for weaving thin and light fabrics such as damask, gauze, and plain silk. This damask loom is commonly used in the southern part of China. One of the places famous for damask production is the Shuanglin region in Huzhou City, Zhejiang Province. Damask produced in this region is celebrated for its softness and luster. Early records show that damask fabrics formed part of the tributes to the imperial court as early as the Tang Dynasty. Such damasks would have been woven on this type of drawloom using the local jili silk. (Long Bo)

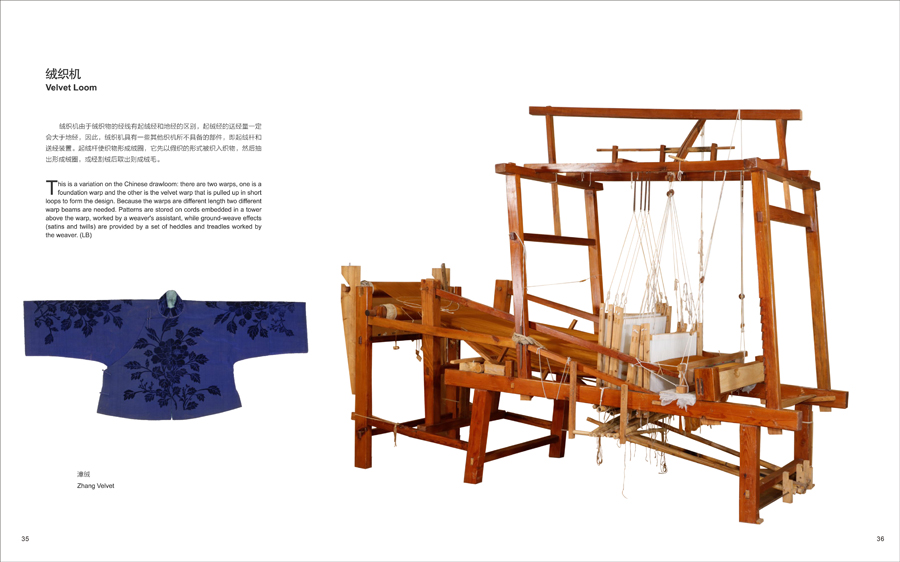

Velvet Loom

This is a variation on the Chinese drawloom: there are two warps, one is a foundation warp and the other is the velvet warp that is pulled up in short loops to form the design. Because the warps are different length two different warp beams are needed. Patterns are stored on cords embedded in a tower above the warp, worked by a weaver’s assistant, while ground-weave effects (satins and twills) are provided by a set of heddles and treadles worked by the weaver. (Long Bo)

Zhang Velvet

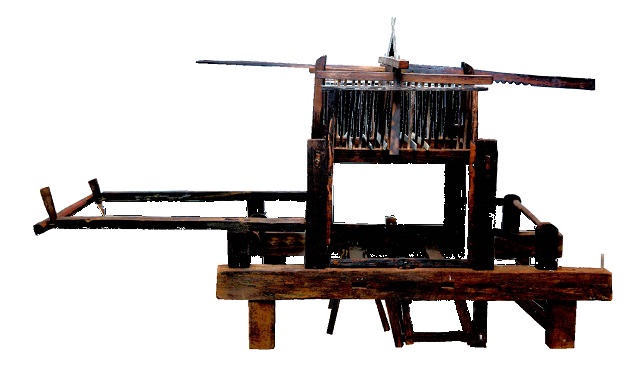

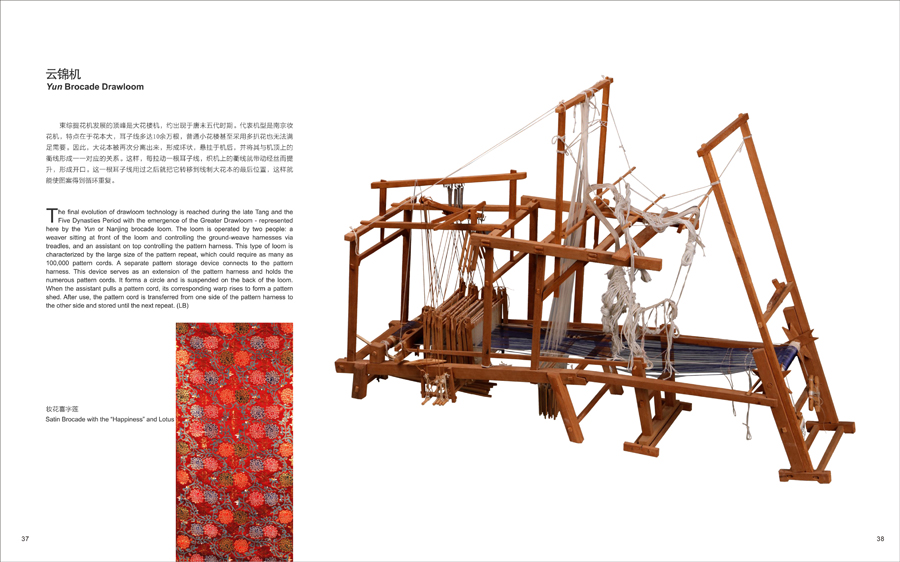

Yun Brocade Loom

The final evolution of drawloom technology is reached during the late Tang and the Five Dynasties Periods with the emergence of the Greater Drawloom—represented here by the Yun or Nanjing brocade loom. The loom is operated by two people: a weaver sitting at front of the loom and controlling the ground-weave harnesses via treadles, and an assistant on top controlling the pattern harness. This type of loom is characterized by the large size of the pattern repeat, which could require as many as 100,000 pattern cords. A separate pattern storage device connects to the pattern harness. This device serves as an extension of the pattern harness and holds the numerous pattern cords. It forms a circle and is suspended on the back of the loom. When the assistant pulls a pattern cord, its corresponding warp rises to form a pattern shed. After use, the pattern cord is transferred from one side of the pattern harness to the other side and stored until the next repeat. (Long Bo)

Brocaded Satin with Happiness and Lotus, Ming Dynasty (replica)

2. EASTERN ASIA: KOREA AND JAPAN

All Japan, Korea and east coast of China belong to one textile cultural circle. Back strap loom was used first, then the woji in China, izaribata loom in Japan and bettle in Korea, also called back strap treadle loom, on which natural shed was made by the thick sticker, and the other count shed by one shaft. It was a dominant type of loom during the Han to Tang Dynasties (1st - 9th centuries), however, more types of loom were also used afterwards, including the Jacquard loom was introduced into China. (Zhao Feng)

2.1 Backstrap Treadle Loom From Buyeo, Korea

This type of backstrap loom, called bettle, has a long history in Korea. To this day, it is still used for weaving a tabby fabric in silk, hemp, cotton, and ramie. Occasionally, it is also used to make ribbed gauze fabrics. For weaving a ribbed gauze, the loom would have two heddle rods. (Sim Yeunok)

3. MAINLAND SOUTHEAST ASIA

Mainland Southeast Asia, also known historically as Indochina, comprises Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, and West Malaysia. Nearly all weaving is done by women, who pass on the traditions of weaving to their daughters, from the sumptuous ikats of the Cambodian royal court of the 19th century, to the fantastical animal motifs of northern Laos, to the fine brocade robes of Vietnamese mandarins. It is evidenced that the oldest form of loom found widely in Southeast Asia was the backstrap loom, probably introduced in during the third millennium BCE. The influence of Chinese and Indian cultures was associated with the changes in textile technology. (Irene Lu)

Lao Loom with Vertical Pattern Heddles

From the market at Vientiane around 1993 Gift of Mary Connors

The Lao Tai groups use variations of a frame floor loom to produce elaborate textiles of tapestry, twill and plain weaves. Their cloth may be embellished with supplementary warp threads, as well as continuous and discontinuous supplementary weft threads. They have a two-heddle system to create and store intricate designs that enable the pattern "code" to be used and reused. The pattern is stored in the vertical heddle with bamboo or string pattern rods. This technology allows the weaver to preserve her creative expression realized in her laboriously picked design. The stored pattern is an important part of her heritage and can accompany her when she marries or travels; the original mobile app. (Carol Cassidy)

Coffin Screen

Tai Daeng People, Sam Neua Province, Laos Gift of Mary Connors

Thailand Weft Ikat Loom

From: Phu Phan, Sakon Nakhon Province, Thailand

Ikat weaving is famous in Thailand. This is a weft ikat loom from Thailand. To make a weft ikat, the weft threads are first wound around a frame called lak mii, whose width reflects the desired width of the final textile. Sections of the weft are then wrapped with continuous yarn, which acts as a resist in the dyeing process. These sections, called lam, correspond to the pattern steps in the final design. Varying the number of yarns per lam creates different visual effects. (Irene Lu)

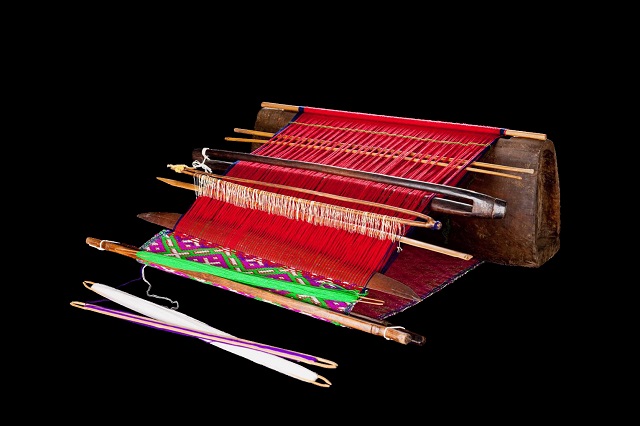

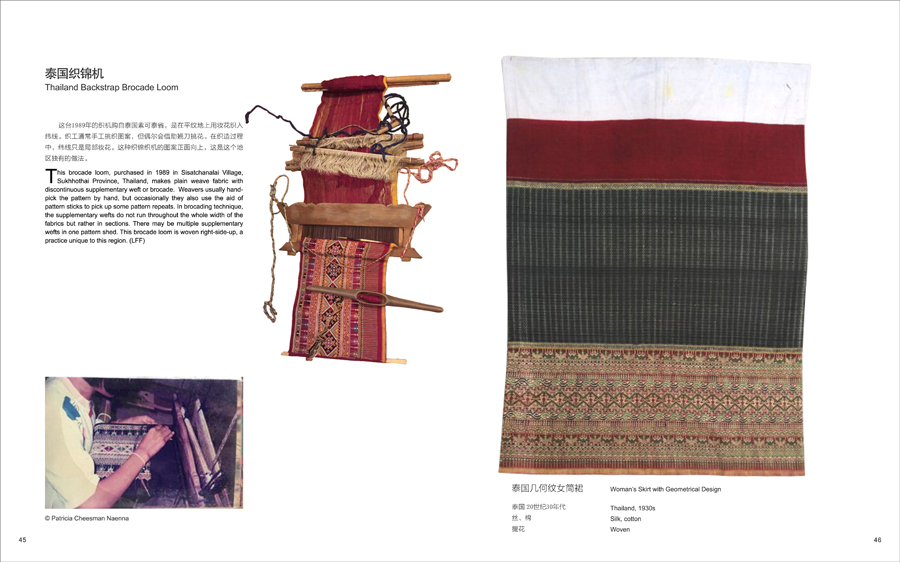

Thailand Backstrap Brocade Loom

Tai Phuan people Sisatchanalai Village, Sukhhothai Province, Thailand, 1989

This brocade loom makes plain weave fabric with discontinuous supplementary weft or brocade. Weavers usually hand-pick the pattern by hand, but occasionally they also use the aid of pattern sticks to pick up some pattern repeats. In brocading technique, the supplementary wefts do not run throughout the whole width of the fabrics but rather in sections. There may be multiple supplementary wefts in one pattern shed. This brocade loom is woven right-side-up, a practice unique to this region. (Irene Lu)

© Patricia Cheesman Naenna

Woman’s Skirt with Geometrical Design, Thailand, 1930s

Silk, cotton, Woven

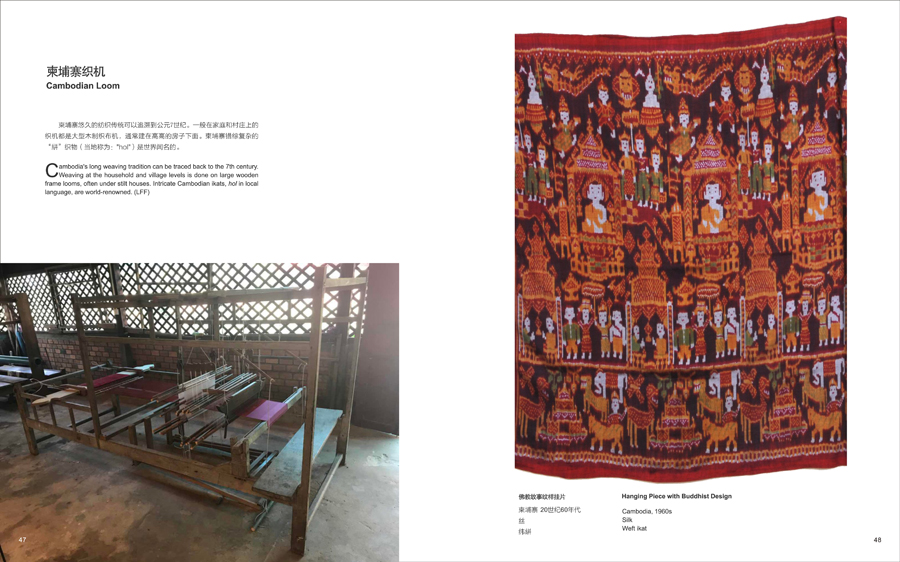

Cambodia loom

Cambodia's long weaving tradition can be traced back to the 7th century. Weaving at the household and village levels is done on large wooden frame looms, often under stilt houses. Intricate Cambodian ikats (hol) are world-renowned. (Irene Lu)

Hanging Piece with Buddhist Design

Cambodia, 1960s, Silk, Weft ikat

Vietnam loom, North Vietnamese

Red River Delta 1950s Gift of Vu Cao Trung from Viseri

Today, weaving in Vietnam is rapidly becoming mechanized, with industrial looms dominating textile production. This is a modern loom for producing rough silk fabrics. (Irene Lu)

4. INSULAR SOUTHEAST ASIA

The Insular Southeast Asia, which includes Singapore, Brunei, eastern Malaysia on north Borneo, Indonesia, East Timor, and the Philippines, is well known for its textile traditions. Textiles woven in these island countries exhibit a range of types from simple stripes to elaborate designs created through supplementary techniques, floats, and ikat. These variations illustrate the history of the Southeast Asia’s past migrations and trades, but they also tell the stories of women. Because here, weaving is a gendered occupation, whereby its knowledge is passed down from mothers to daughters.(Sandra Sardjono)

Backstrap Loom with Geringsing Textile

Tenganan Pegringsingan Village, Karangasem, Bali, 2018

Loom by I Made katung; wood from jackfruit tree

Woven by Ni Luh Kembang: cotton, natural dyes; double ikat

Geringsing Wayang Putri Textile

Tenganan Pegringsingan Village, Karangasem, Bali, purchased in 2018

Woven by Ni Nyoman Diani

Cotton, natural dyes; double ikat

Tenganan Pegringsingan is the only place in Indonesia where double ikats are made. Its technique requires both the warp and the weft to be tie-dyed prior to weaving. The geringsing loom is a backstrap loom with two plain-weave heddles and double-ikats on display were produced through the collaboration of several individuals within an extended family. (I Putu Cobby Wiryadi)

Backstrap Loom with Bulang Textile

Nagori Tongah Village, North Sumatra, 2018

Loom by Obersius Damanik

Textile by Ompu Elza, boru Sinaga, Nyonya Sitanggang

Wood from sugar palm, cotton, natural dyes; supplementary weft and warp

Loom width: 60 cm; Textile width: 33 cm

Woman’s Headdress, Bulang Textile

Nagori Tongah village, North Sumatra, 2018

Woven by Ompu Elza, boru Sinaga, Nyonya Sitanggang

Cotton, natural dyes; supplementary weft and warp

Dimensions: 33.5 x 213 cm

The bulang is one of the most complex Simalungun textiles with supplementary warp patterning in the red center field, and supplementary weft in the white end fields, produced in the village of Nagori Tongah. The transition from red to white warp in the cloth is executed on backstrap loom using a rare technique called warp substitution. When the red warp is half woven, the weaver 'sows' in the new white warp, cuts out the unwoven red warp, and continues with the white warp. (Sandra Niessen)

Wrap Ikat Backstrap Loom

Rende Village, East Sumba, 20th century

Wood, handspun cotton, natural dyes; warp ikat

Loom width: 127 cm; Textile width: 57 cm

Gift of Sandra Sardjono

The Sumba loom on display is used for weaving a warp ikat textile for a man’s cloth known as hinggi kombu. What is currently on the loom is only one half of a hinggi. A complete cloth would require two identical textiles, which would be seamed together along the selvages. Notable features of this Sumba loom are the warp beam and the cloth beam. Here they consist of double wooden rods with finials in the shape of a horse. (Sandra Sardjono)

5. INDIA

India is the world’s last remaining textile bastion where handlooms continue to operate at a more or less industrial scale. The majority of Indian handloom traditions are simple, two or four-shaft tabby looms. These are however very diverse in terms of typology, operation, fabric design as well as the end product. At the other end of the spectrum lie the complex looms that produce India's famed patterned silks. These incorporate the well-known jacquard mechanism as well as several traditional draw-harness mechanisms.

Another unique feature of the Indian handloom landscape is how the weaving techniques developed over last several centuries continue to be in operation simultaneously and often in conjunction with each other. A number of these techniques are likely indigenous while many others have been acquired from numerous weaving traditions of the world. (Hemang Agrawal)

Jaala Loom

The jaala drawloom in Varanasi has a warp beam and uses a separate set of treadles to control the lifting and the depression shafts. The structure harness consists of jack-type wooden shafts, and the pattern harness consists of horizontal cross-cords that hold groups of warps with string leashes. The key component of this drawloom is the naqsha, installed at the upper level of the loom. It is a detachable set of vertical drawcords and horizontal pattern lashes that acts as a template for pattern lifting. The vertical drawcords are knotted to the horizontal cross-cords of the pattern harness. (Hemang Agrawal)

Sari From Varanasi, India 1980s

Pit Loom

The pit loom is the earliest known treadle loom in India. The loom always has pairs of heddles and treadles (either 2 or 4). They are operated using a pulley or roller system to form the sheds. The name of the loom comes from the pit that is dug to accommodate the weaver’s legs and the treadles. Weaving inside the pit causes the warp yarns to be close to the ground, allowing them to absorb moisture from the cool earth, which resulted in better weaving. This loom is mainly used for producing thin cotton fabrics and also thick flat-weave rugs. (Long Bo)

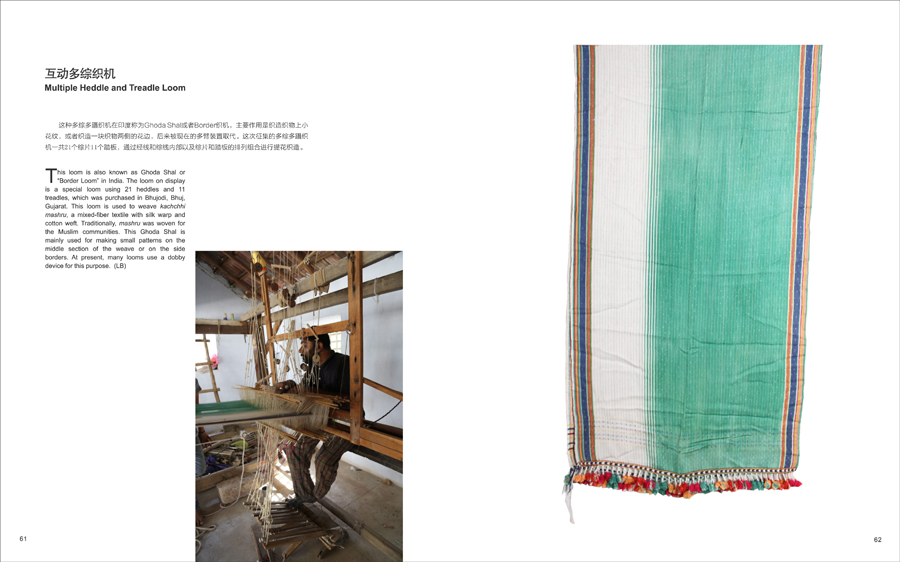

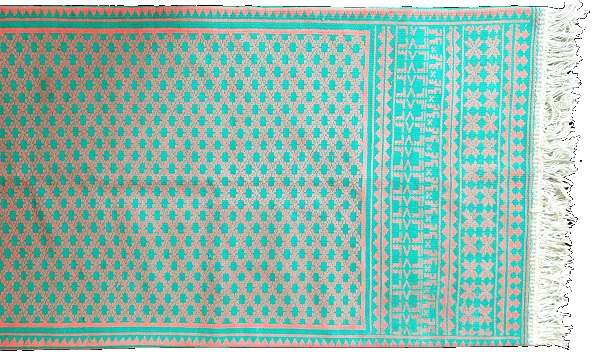

Multiple Heddle and Treadle Loom

This loom is also known as Ghoda Shal or “Border Loom” in India. The loom on display is a special loom using 21 heddles and 11 treadles, which was purchased in Bhujodi, Bhuj, Gujarat. This loom is used to weave kachchhi mashru, a mixed-fiber textile with silk warp and cotton weft. Traditionally, mashru was woven for the Muslim communities. This Ghoda Shal is mainly used for making small patterns on the middle section of the weave or on the side borders. At present, many looms use a dobby device for this purpose. (Long Bo)

6. CENTRAL AND WESTERN ASIA

There is evidence in Central and Western Asia for woven textiles that date back at least 7,000 years. Over the following centuries there is more certain evidence for the existence of looms and these can be divided into two basic types, namely horizontal (ground) and vertical (upright) forms. The horizontal loom includes pit and raised types. The vertical loom appears to be simple frames that had the warp threads stretched between the top and lower beams. Sometimes these frames were used for making mats, while other loom forms were capable of making much more complicated woven forms. (Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood)

Beduin Loom

The earliest illustration of a ground loom appears on the side of the flat bowl dated 4000 BCE, found at Badari in Central Egypt and now in the Petrie Museum, University College, London. A similar loom is depicted in the Middle Kingdom wall painting of the Eleventh Dynasty c.2020 BCE. Both show the warp stretched out between two beams which are held in position by four pegs stuck in the ground, two at each end. This same simple ground loom is still used today in several parts of the world, but especially in the areas occupied by the Bedouin. This loom was made by the Bedouin people who lives in the Negev Desert in the Middle East. (Zhao Feng)

Zilu Loom From Meybod, Iran

An Iranian zilu loom in Meybod is essentially a vertical form. It consists of a frame made from two large upright posts, both with a forked top. These two posts carry a cylindrical warp beam. At the bottom of the loom is the cylindrical cloth beam. A zilu loom can vary in size from about 200 cm to over 600 cm in length and about 300 cm in height, depending on whether mats are being made or carpet size examples. (Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood)

Zilu weaver at work on a loom in Meybod (2001; photograph by Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood).

Zilu floor covering From Meybod, Iran

Cotton, synthetic dyes; weft-faced compound tabby (taqueté)

Gift of the Textile Research Centre, Leiden, The Netherlands

7. EUROPE

The two loom types mainly discussed as relevant to the European context are the two-bar vertical loom and the warp-weighted loom. It has been suggested that the two-bar vertical loom originated in Syria or Mesopotamia, but the earliest visual representation occurs in Egypt during the last part of the 2nd millennium BCE. It has also been proposed that this loom could have been developed in connection with the introduction of wool.

A warp-weighted loom is upright and is placed leaning against a wall or a beam in the roof. When weaving, one stands in front of it and weaves from the top down. The weft is beaten upwards. The vertically hanging warp threads are kept taut by the attached loom weights and shed bars and heddles are used to separate sheds which makes this loom type especially useful for twill weaving. (Eva Andersson)

Warp Weighted Loom

The warp-weighted loom has been used in many parts of Europe and the Near East for a long time. Its early use is confirmed by numerous archaeological findings of loom weights. These weights are made of either clay or stone and vary in size and shape depending on the region and the period. Elisabeth Barber has suggested that the warp-weighted loom was already in use in Central Europe—in Hungary and perhaps Anatolia—in the 6th and maybe the 7th millennium BCE, i.e., in the early Neolithic period. During the Bronze Age, the use of this loom expanded into Greece and Northern Italy, and further to the west (for example Switzerland) the United Kingdom and later to Scandinavia. (Eva Andersson)

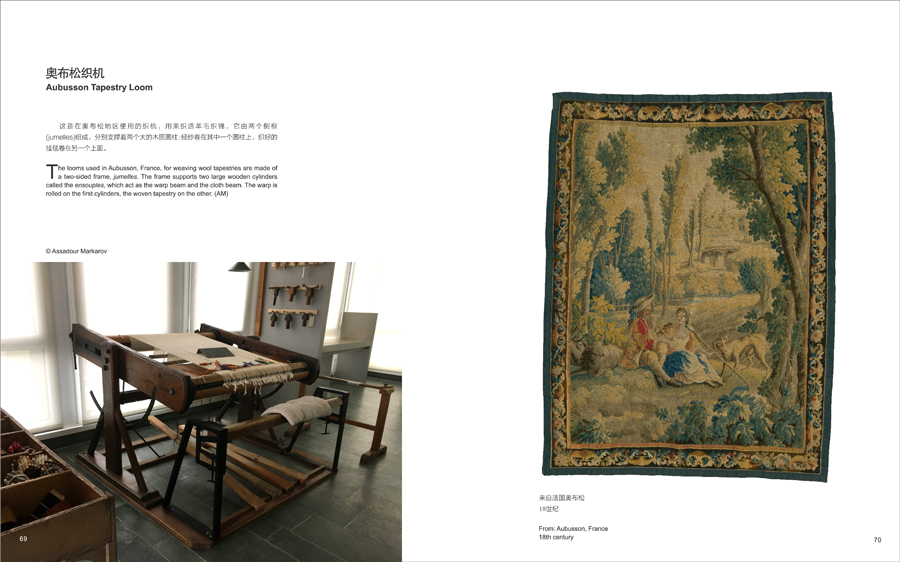

Aubusson loom From: Aubusson, France, 18th century © Assadour Markarov

The looms used in Aubusson, France, for weaving wool tapestries are made of a two-sided frame, jumelles. The frame supports two large wooden cylinders called the ensouples, which act as the warp beam and the cloth beam. The warp is rolled on the first cylinders, the woven tapestry on the other. (Assadour Markarov)

8. SOUTH AMERICA

Simple looms, basically composed of two sticks to hold the warp, were used in the Andes for weaving from 2500 BCE to the present day. Yarns interlaced in perpendicular orientation, using single, double and even triple sets of warps or wefts (or both) resulted in some of the most complex textile structures known throughout the world. These woven fabrics, composed of the native cottons and camelid hairs from the llama, alpaca, and vicuña, were used as garments in daily or ritual and ceremonial life. Patterning relied on the mind and memory of the weaver, rather than loom mechanisms. In a culture with no writing, the Pre-Columbian weavers drew from historical knowledge, passed down from generation to generation. (Elena Phipps)

Peruvian Backstrap Loom

Chinchero, Peru, 21st century

Sheep’s wool, alpaca hair, natural dyes; warp-faced, warp patterned weave

This backstrap loom has the components of a traditional Andean loom: the wooden loom bars, notched at each end. On one end a belt would be attached and tied around the weaver’s waist. On the other, there would be a cord that is tied to a fixed pole or tree to secure the warp tension. For weaving the plain weave sheds, one shed bar maintains the first open shed, and a set of heddles maintains the second. The yarn heddles are created after the warp is on the loom and attached to a small rod. Additional shed sticks may aid the weaver for creating the patterns, though these are usually created individually, by hand-selecting the yarns to form a complementary two-faced weave.

The partially woven textile is half of a woman’s shoulder mantle with warp-faced and warp-patterned weaving. The patterning is formed in the long, narrow vertical stripes composed of different color yarns (often laid out in pairs) that are placed on the loom during the warping process. The weaver creates the pattern from memory, sometimes using an existing mantle as her guide. The sharp bone tool is used the pack the weft yarns within the densely set warp. A finished mantle is woven in two parts, sewn together down the center. (Elena Phipps)

9. AFRICA

Looms can be found all over Africa and cloths are still hand-woven in large quantities. These fabrics often have high prestige value. Extensive trade in these textiles in and beyond this vast continent has been ongoing for many centuries. In Egypt, weaving can be dated back to at least pre-dynastic times (before 4000 BCE) and this might be true for other areas, but much research still needs to be done. In West Africa, the oldest archaeological evidence so far of cloth production dates to the 800s and 900s, in present-day Nigeria and Mali respectively. Weaving in most of West Africa, East Africa, DRC, and Ethiopia is primarily done by men, while in Berber North Africa and Madagascar, only by women. In areas such as Arab North Africa, the Sudans and Nigeria, both men and women weave but they mainly weave on different types of looms. (Malika Krammer)

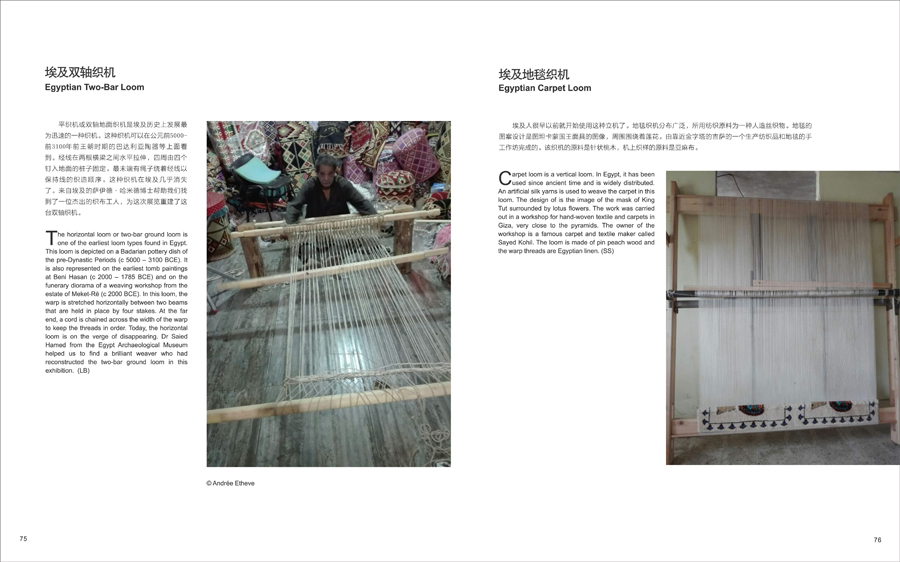

Two-bar Loom from Egypt

The horizontal loom or two-bar ground loom is one of the earliest loom types found in Egypt. This loom is depicted on a Badarian pottery dish of the pre-Dynastic Periods (c. 5000–3100 BCE). It is also represented on the earliest tomb paintings at Beni Hasan (c. 2000¬–1785 BCE) and on the funerary diorama of a weaving workshop from the estate of Meket-Rē (c.2000 BCE). In this loom, the warp is stretched horizontally between two beams that are held in place by four stakes. At the far end, a cord is chained across the width of the warp to keep the threads in order. Today, the horizontal loom is on the verge of disappearing. Dr Saied Hamed from the Egypt Archaeological Museum helped us to find a brilliant weaver who had reconstructed the two-bar ground loom in this exhibition. (Long Bo)

Carpet Loom from Egypt

The vertical loom was used by Egyptians since the ancient time. Carpet loom is one kind of vertical loom which was widely distributed. An artificial silk fabric was used to wave the carpet sample in this carpet loom from Egypt. The design of the carpet is the Image of the mask of King Tut surrounded by the lotus flower. The work was carried out at a workshop for making manual textile and carpets in Giza very close to the pyramids. The owner of this place is the most famous manual carpets and textile makers in Egypt who is called Sayed Kohil. The loom was made of pin peach wood and linen Egyptian fabric was used for weaving the sample. (Long Bo)

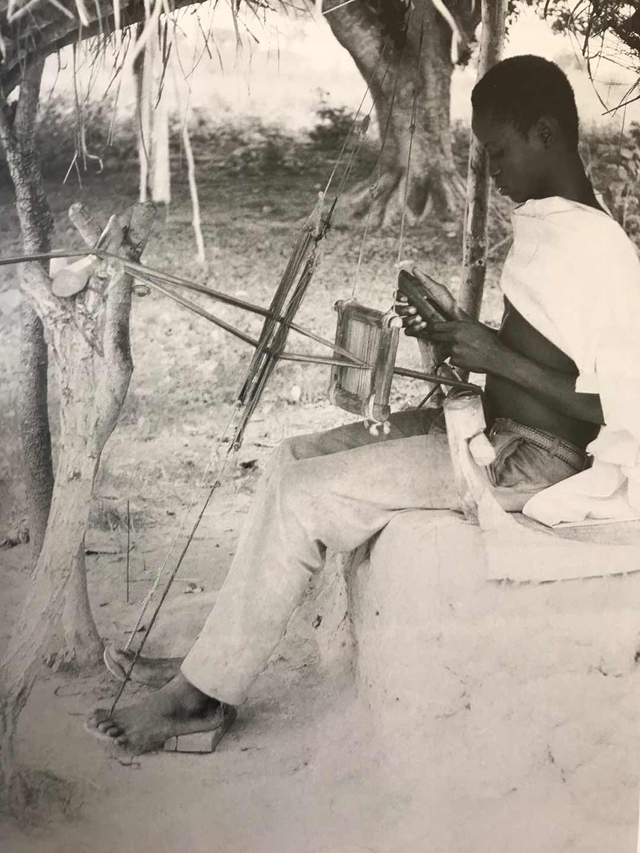

Ghana Looms

In Ghana, like in many other West African countries, the double-heddle loom is used to make predominantly warp-faced narrow strips, which are then sewn together to form a cloth. In southern Ghana, both in the Asante and Ewe-speaking region, this loom type has two or three pairs of heddles. With these simple devices, weavers are able to create ingenious patterns with alternating weft-faced and warp-faced structures, often with weft-float motifs.

The Asante loom shares more features with looms to the north and west, while the Ewe loom bears more similarities with looms further to the east. The fixing of the cloth beam, as well as the counting systems and method for laying the warp, are different in these two looms. Fabrics woven on these looms are called kente cloths. The history of the two type of looms and the wide variety of textile designs produced on them have independent as well as interrelated histories that can be traced back to at least the 1600s. They are the most famous cloth from West Africa with such distinct design that these are printed in large quantities, in particular in China, for export to Ghanaian, other African and American markets.

One of the most complicated techniques employed on the Asante loom is the use of three pairs of heddles. In the Ewe region, weavers have a long tradition of weaving with two sets of warps, producing supplementary warp-faced textiles. The two looms on display show these two different techniques. (Malika Kraamer)

Madagascar Looms

Madagascar lies off the coast of East Africa and is the fifth largest island in the world. Malagasy textiles vary depending on their production area. Nomadic populations, such as the Sakalava group of the west and northwest coast, and sedentary populations of the Highlands produce very different fabrics. In Madagascar, we can find several loom types. The most common type has a single-heddle that is fixed and suspended and a continuous warp between two beams.

Although double-heddle looms can also be found, they are rarely mentioned in older reports on Madagascar. Depending on the region, either one or both planes are woven at one time. In the first case, one beam is loosened at intervals, and the already woven cloth pulled around, in a similar manner as is done in Nigeria. In the other case, the resulting cloth is the same length as the distance between the two beams, and the heddle needs to be moved along the cloth as weaving progresses. Some groups in the southeast of Madagascar use a backstrap loom, whereby the tension in the warp is provided by the weight of the weaver. This feature is unique in Africa, although common in other parts of the world, especially in Southeast Asia.

Three looms with characteristic weaving techniques from three remote locations are presented here; they represent the ancestral heritage of Madagascar. (Malika Kraamer, Andrée Etheve)

Loom for Akotifahana Textiles

From high lands, around the capital city Antananarivo

This type of loom, found throughout the center of Madagascar, consists of a simple frame on legs, which allow seated weaving. This is the loom for akotifahana, Madagascar historic brocades. The pieces produced measure around 2.5 x 0.9 m. The row of string heddles called haraka allows for the lifting of the warp threads for the plain-weave ground. The loom is also equipped with extra heddles for the supplementary weft patterns. The weaver of the partially woven cloth on the exhibition is an heir of a long line of artisans from the village of Amboditrabiby, 30 km from the capital city. (Andrée Etheve)

© Andrée Etheve

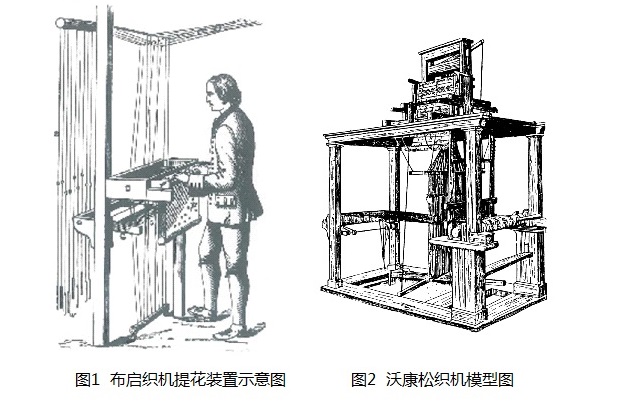

10. JACQUARD LOOM

A Jacquard loom is a loom set up with a card-reading machine: the Jacquard machine. It was not until 1817 that the Jacquard machine ran efficiently. It works using punched cards on which each hole is matched with one warp yarn. For instance, if the spot for number 35 hole is punched, the yarn number 35 will lift up; if the spot is not punched, the yarn remains stationary. These cards are punched beforehand according to the design and the point paper plan and bound to constitute a string. This "original" wooden Jacquard machine was in use until the mid-20th century. Today, we turn to the digital Jacquard machine. (Guy Scherrer)

French Jacquard Machine

This 19th-century Jacquard machine may have 1200–1300 independent commands. Since a fabric has around 8000–10,000 warp yarns, the loom uses shafts with heddles to group several yarns into one independent command. In contrast, an electronic Jacquard machine may have 26,000 independent commands, and, therefore, do not need shafts. The "original" wooden Jacquard machine reads punched cards. The cards are punched according to the design and the point paper plan.

The Jacquard machine uses a binary code: a hole means the yarn moves up, an absence of hole means it stays in place. In term of the mechanics of the machine, the holes in the cards control some horizontal needles, and the movements of these needles control some vertical hooks that are tied to necking cords and heddles. If there is a hole, a needle goes through it, and the hook remains stationary. In this position, the hook is caught by a rack system and lifted up. Consequently, the corresponding necking cord, heddles, and yarn are raised. If the needle hits the card face with no hole, the card pushes the needle, and the needle pushes the hook. As a result, the rack does not catch the dislocated hook, and the heddle doesn't move. One card is used for each shuttle shot, so the number of cards corresponds to the length and the fineness of the design. (Guy Scherrer)

Chinese Jacquard Machines: The development of Jacquard looms in China

The Jacquard loom was introduced into China via Japan at the end of the Qing Dynasty and the early years of the Republic of China. The Japanese had improved it before the loom was brought to the Jiangsu and Zhejiang Provinces in 1910. The Jacquard loom was equipped with a Jacquard shedding device and hand-pulling ropes for controlling the movement of the sheds. Around the city of Suzhou, this loom was known as “Tieji, or iron machine.” In 1915, the Shanghai Zhaoxin silk factory started by Shen Huaqing introduced nine Swiss-made electric looms for weaving silk; these were the first automatic looms in China. By the 1950s, many types of electric looms were in use in China, such as rapier loom, air-jet loom, gripper loom, and water-jet loom. With the disappearance of the traditional wefting (weft-insertion) using shuttle, the production output of loom increased exponentially. By the 1970s, with the advent of multi-phase loom, the design idea of continuous wefting began to replace that of intermittent wefting. (Lu Jiangliang)

Huzhou Hyundai Computer High Speed Jacquard Weaving Loom

This is a model of high efficiency computer jacquard rapier weaving loom adopted in modern silk weaving industry, which is an excellent model assembled by three famous textile machinery manufacturers in domestic and oversea market.

Base loom:Adopting E58 serial advanced rapier weaving loom, which is designed and developed by PANTER Italy, all techniques developed by PEZZOLI family who is the father of Italian rapier weaving machine. The machine is famous for its high speed, high efficiency, maximum versatility, lower energy consumption and simple operation in the world. The minimum rapier design and the smallest shed opening in the world making PANTER become the best weaving machine on weaving all kinds of silk products with fine fiber, owning very high running efficiency and very low warp yarn breaking rate.

Jacquard:Developed by the best jacquard manufacturer in the world —— Staubli International AG, which is a French high technology enterprise with long history. The jacquard owning excellent stability, low energy consumption and low failure rate under high speed running circumstance with long using life. It is the best choice of shed opening device for all kinds of jacquard fabrics.

High density weaving unit:With around 40 years professional experience of producing thigh density weaving machine and device, (JULIBAO)HUZHOU HYUNDAI TEXTILE MACHINERY make a serial refitting on base loom, such as adding full width temple, screw pole and ironing device, making the whole machine dramatically improve the fabric density of general jacquard weaving machine. The ironing device equipped on machine makes the fabric flatter, substantially shortening the time of procedures even making label, drawing craft, woven shoes upper, any kind of high density fabric. (Lu Jialiang)

Pay attention to us

×

Pay attention to us

×