Exhibition place:Temporary Gallery, China National Silk Museum

Exhibition time:2019.6 - 2019.9

Foreword

The ancient Silk Road is like a ribbon, connecting ancient China with other countries in the world. It is through the Silk Road that Chinese sericulture, silk, tea, ceramics and the like spread to countries all over the world. Meanwhile, Central Asian horses and grapes, Indian Buddhism, music, method of sugar manufacture, and medicine, Western Asian musical instruments, gold and silver wares, astronomy, and mathematics, and various material culture and technology of Asian islands, European countries, and even the African continent were also imported into China, enabling the ancient Chinese civilization to be constantly updated and developed.

However, the factors that played decisive roles on the Silk Road are people. Whether they were envoys, merchants, herdsmen, sailors or priests who traveled along the Silk Road, or soldiers, officials, farmers, bailiffs at courier stations, monks who worked on the Silk Road, they were the true builders, guardians, and witnesses of the Silk Road. This exhibition tries to reshape the life along the Silk Road by concentrating on 13 individuals who lived at different times, had mixed nationalities, maintained diverse identities, and gained unlike life experiences. These people either legendary or ordinary. Their daily life and mundane experience unfolded the “great era” of peace, cooperation, openness, and inclusiveness, and thus reproduced the time characteristics and the collision of cultures under different eras along the Silk Road through many perspectives.

Thanks to the British scholar Susan Whitfield for allowing us to borrow her book title “Life along the Silk Road” as the exhibition name.

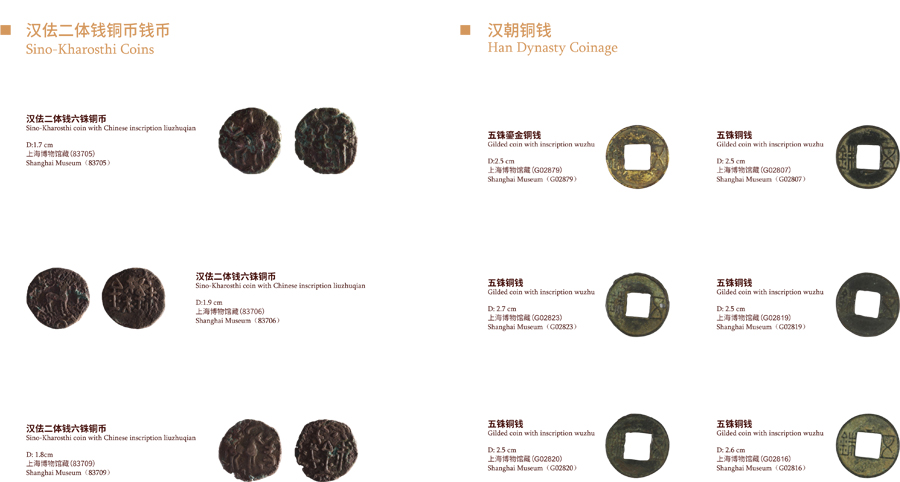

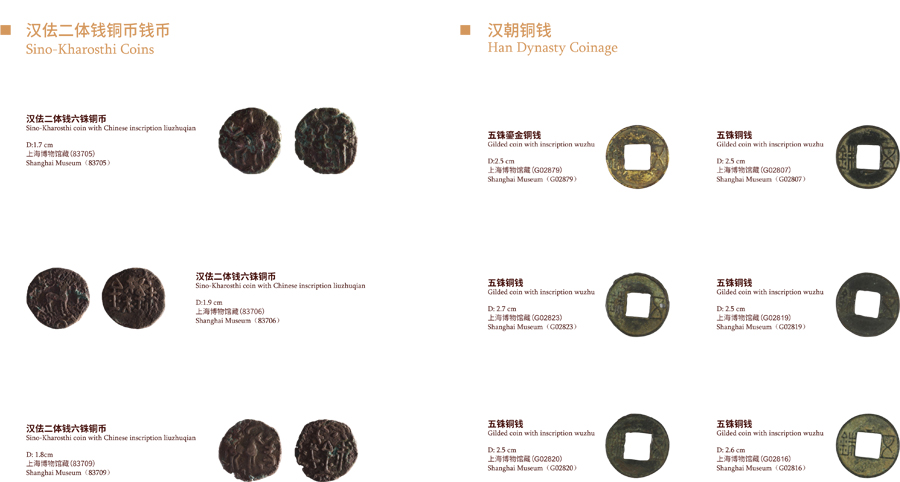

Prologue: History Revealed through Coins

The Silk Road was a network of trading routes across the Eurasian continent. If trade was the driving force of the Silk Road, then the ancient coins were the witnesses of cultural exchange between the eastern and the western civilizations of Eurasia. The exhibited numismatic artifacts dated from the fifth century BCE to twelfth century, spanning nearly two thousand years of time. The geography of circulation covered entire Eurasia: stretching eastward until the west coast of the Pacific Ocean and reaching westward towards the Mediterranean Sea via the Iranian Plateau. The cast coin of round shape with a square hole in ancient China became the representative of the eastern numismatic culture. With the economic development, the format and usage of Chinese coinage had a profound influence in East Asia. Hammered coinage gradually evolved in the Mediterranean world and Iranian Plateau, and it became a major form of currency in Central and Western Asia. These two kinds of coinage formed their distinctive range of usage. Furthermore, their convergence in the Eurasian heartland engendered a new form of coin that combined the characteristics from both sides. Charged with cultural meanings, these coins reveal a chapter of exchange between the East and West in the Silk Road history.

1.The Saka Warriors

The Pazyryk culture was located in the Altai Mountains and was a very large early nomadic tribe alliance. Because Altai is rich in gold, the Pazyryk people should be the gold guardians in history. The nomadic people wore wool clothes, lived in log cabins, used golden ornaments. The decorations on the ornaments were abundant, however, the law of the jungle was the most popular motif. Their culture influence spread eastward through Yin and Yan Mountains to the entire northern part of China and even penetrated into the Central Plains and the south. Meanwhile, they were located on the key access path of the steppe, so there were many exchanges between the East and the West. The Pazyryk burials were concentrated to the third century BCE and may not belong to the highest-ranking elites. Wool fabrics dyed purple from the sea snails of the Mediterranean coast were unearthed. Besides that, silk products that first went abroad from China were also discovered. The so-called brocade and embroidery route headed to the Eurasian steppe started from this period.

Swan figure

3rd centuries BC

The State Hermitage Museum

Bridle

Cheek-pieces L 21cm and 25cm;

Forks L 12.5cm and 11.2cm;Plaques: H 10-10.5cm

The State Hermitage Museum

Late 4th – early 3rd centuries BC

Finial – deer figurine with antlers

Late 4th – early 3rd centuries BC

H max. 10.5cm; L of deer 5.5cm;

L of antlers max. 8.2cm

The State Hermitage Museum

Horse forehead decoration representing two fantastic eagles

5 centuries BC

D 12.7cm

The State Hermitage Museum

Rug with a decorated border– lions' heads and triangles.

Late 4th – early 3rd centuries BC

L about 135cm W 100cm

The State Hermitage Museum

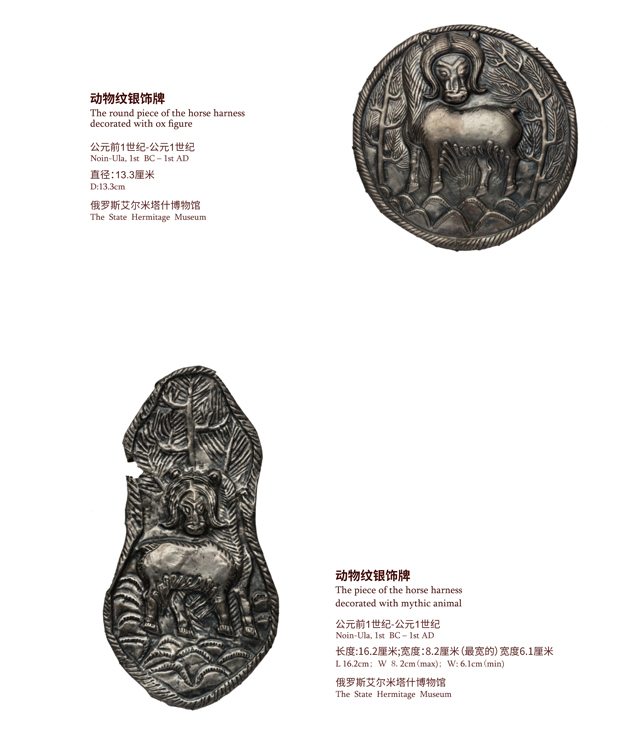

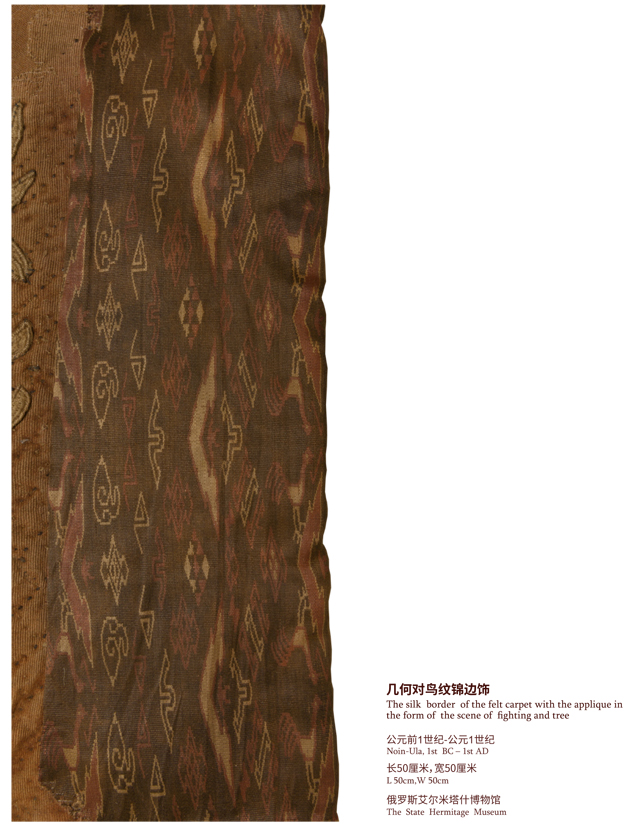

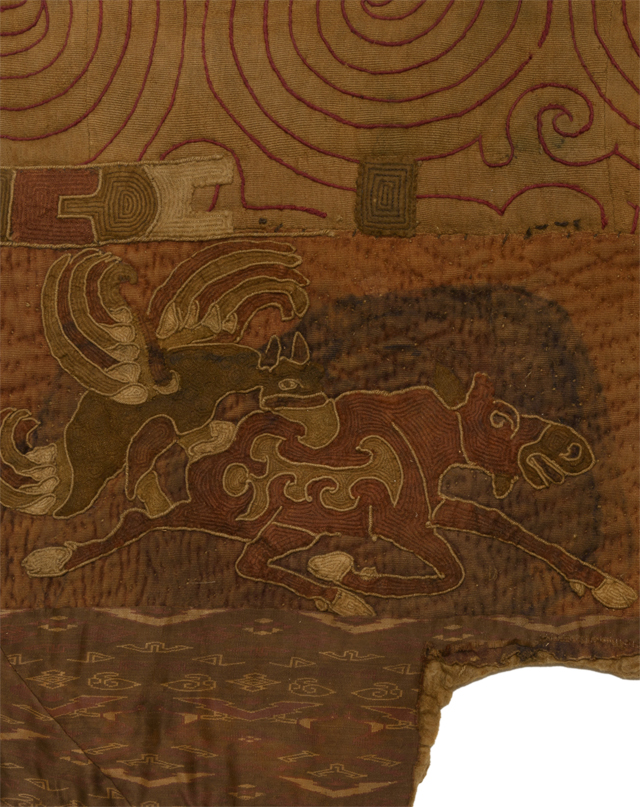

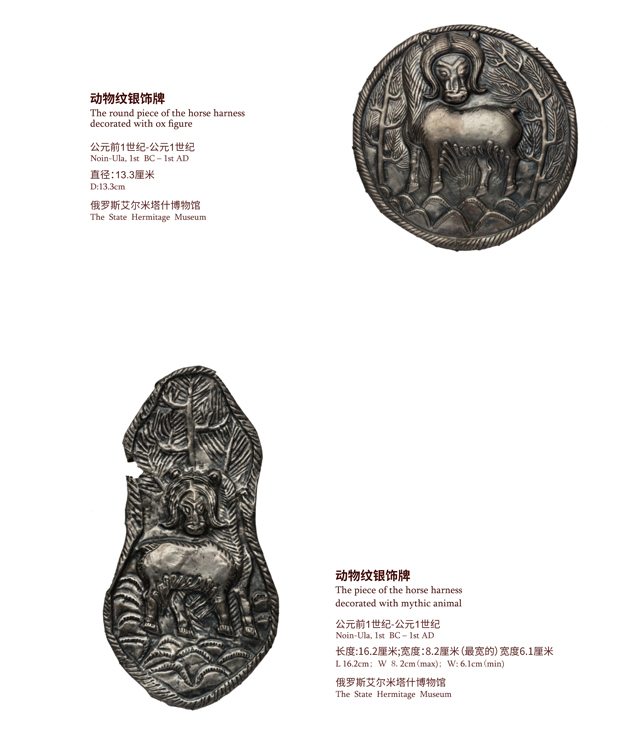

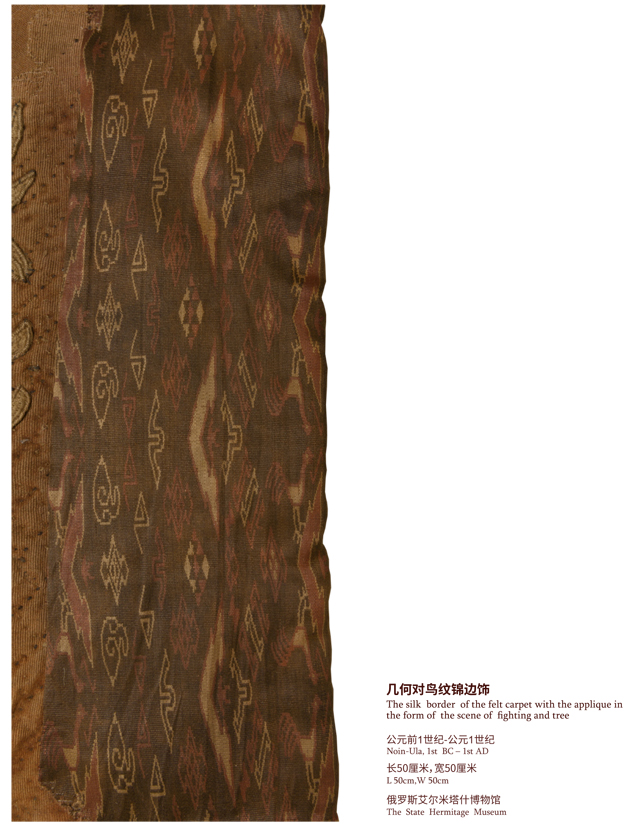

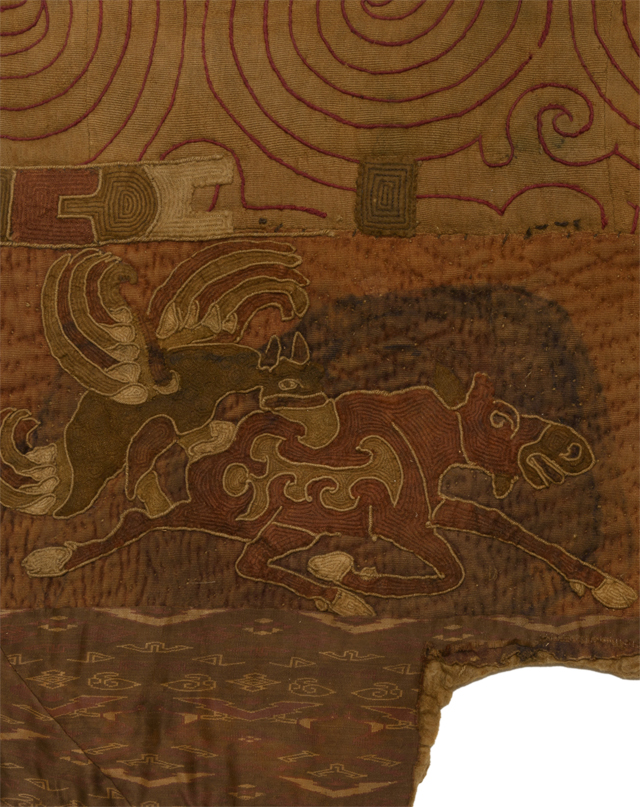

2. The King of the Xiongnu

The Xiongnu was a powerful nomadic tribe in northern China during the Warring States period and the Han dynasty. However, under the attack of the Han dynasty since Emperor Wu, many Xiongnu tribes went south and sought peace with the Han empire. In the second half of the first century BCE, people on the Han-Xiongnu border started to live in peace. The two places had close contact through envoys and enjoyed flourished commerce. A cemetery of many high-ranking Xiongnu elites around the first century BCE was discovered in Noyon Uul Valley of Mongolia in 1912, which was the witness of the reconciliation between the Xiongnu and Han, and the smooth Silk Road in this period. The unique burial style imitated the tomb structures of the Western Han marquises, and the coffins were assembled with traditional mortises and tenon joints of the Han dynasty. The grave goods in the tombs also vividly depict the life of the Xiongnu elites: they were very fond of all kinds of jade, bronze and lacquer artifacts presented by the Han empire. One of the lacquered cups had the inscription “[Made in] the fifth year of the Jianping reign period of Emperor Ai during the Han dynasty [2 BCE]”. Jia Yi said “the senior in Xiongnu families wear embroideries, and the youth wear brocade,” which was evidenced by the large quantities of unearthed silk clothing. The cultural exchange, collision, and integration of the Xiongnu and the agricultural civilization of the Central Plains were important parts of the Steppe Silk Road.

The fragment of the felt carpet with the applique in

the form of a griffon attacking a moose

Noin-Ula, 1st BC – 1st AD

L 83cm,W 60cm

The State Hermitage Museum

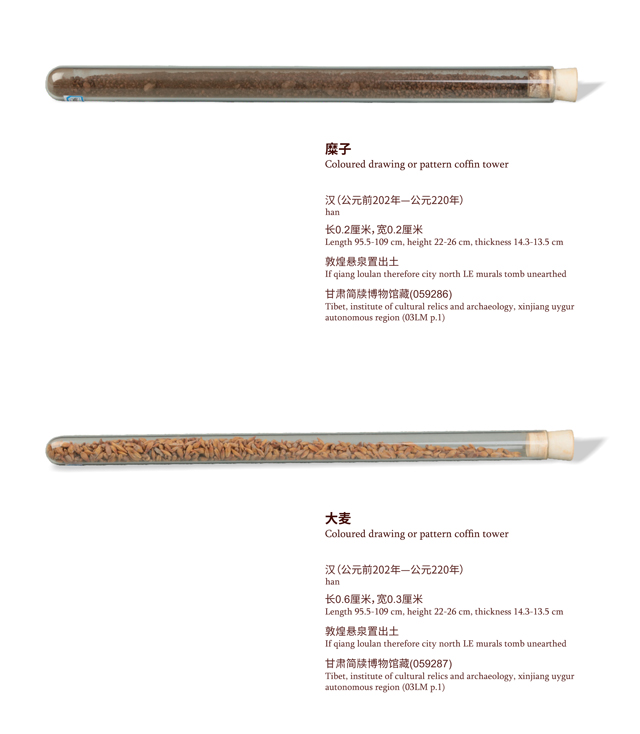

3. Bailiff at a Courier Station

Xuanquan Courier Station was located on the Hexi Corridor. It was mainly responsible for transmitting the official documents of the imperial court and the military information of the soldiers, and accommodating officials and domestic and abroad envoys who passed by. Bailiff at Xuanquan Courier Station was the leader of the agency. In the Han dynasty, the leaders of many grassroots units were collectively referred to as “Bailiff,” and there were many categories, similar to what is said today as “the main leader of the unit.”

Xuanquan Courier Station was located in the northwestern frontier and served as a key station along the Silk Road. In the 200 years, Hong was the longest serving Bailiff at Xuanquan Courier Station, from the third year of the Yuankang reign period (63 BCE) to the fourth year of the Chuyuan reign period (45 BCE), a total of 19 years. Bailiff Hong was probably from Yinongli, Xiaogu County. He was literary and came from a family with assets and land. At the age of 25, Hong was appointed as Bailiff at Xuanquan Courier Station. When he was serving as a Bailiff, many domestic and foreign events involving the Silk Road and the Sino-West had direct or indirect relations with him, such as received Marquis of Changluo Chang Hui when he went to Wusun; experienced the rebellion of Western Qiang; witnessed the Xiongnu Prince Rizhu pledged allegiance to the Han empire; welcomed Princess Jieyou when she went back to Chang’an, etc.

Imperial Edict of 61 B.C.Guochangluohou

Expense Record(18 wooden slips)

Han dynasty (202BC-220CE)

Gansu Bamboo Slips Museum(024660-024677)

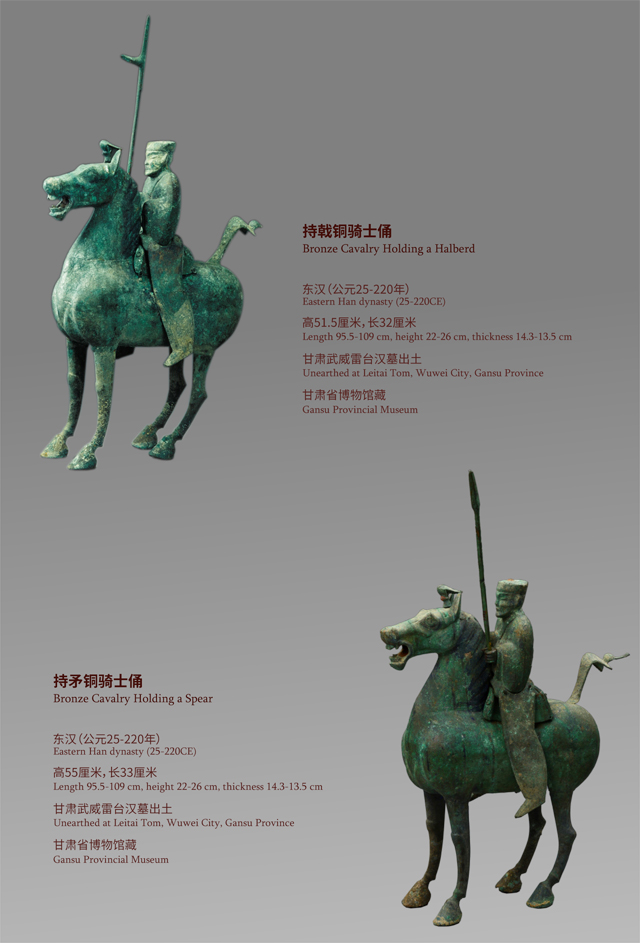

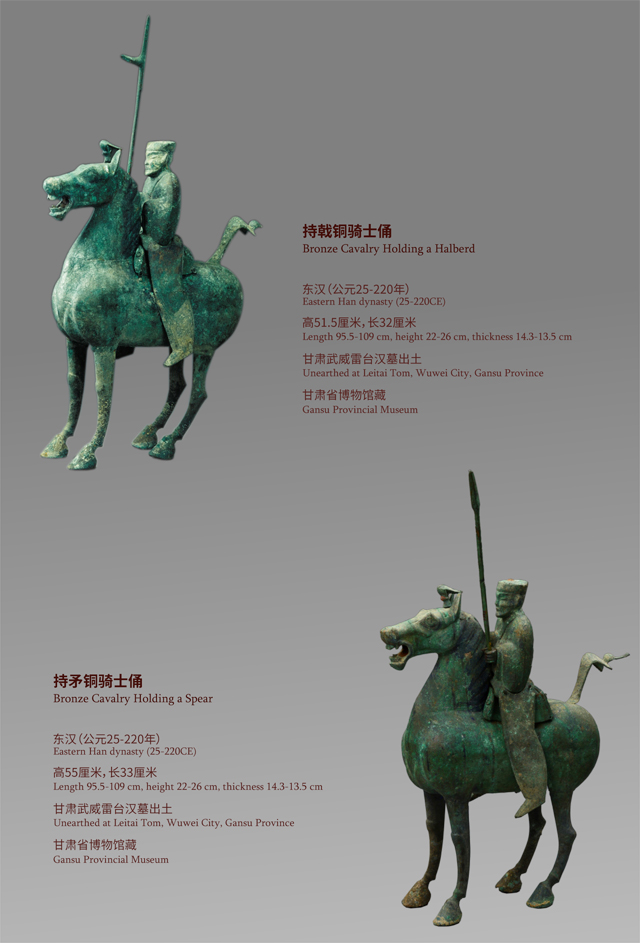

4. District Defender of Hexi

Discovered in 1969, the Leitai tomb of the Han dynasty is located in Xinxian Village, Jinyang Township, Liangzhou District of Wuwei City. “Leitai,” or the Thunder Platform, refers to a rectangular platform named after Leizu, or the God of Thunder, whose image is housed in the rear hall of the Daoist temple called “Leitai guan” on top of the platform.

It is difficult to identify the tomb owner since there is no epitaph in the tomb. The only information available includes the inscription on the horse that reads “one male attendant who drives the chariot and one female attendant that accompanies the carriage of the Mistress of the Front of Mr. Zhang, Chief Commander of Zhangye,” and the inscriptions on the figurines’ back that read “male attendant for Mr. Zhang” and “female attendant for Mr. Zhang”, as well as four silver seals with turtle-shaped knobs. These information show that the tomb occupant was a General surnamed Zhang, who also served as a Commandery Governor of Wuwei Commandery, one of the four commanderies in Hexi region. In academia there are four major opinions regarding the tomb occupant’s identity: A. Zhang Xiu, a famous military official of the Cao Wei kingdom in the Three Kingdoms period; B. Zhang Jun of the Qianliang regime; C. Zhang Jiang, Governor of the Wuwei Commandery in late Western Han period; and D. surnamed Zhang, served as the Battalion Commander of Left Cavalry in Wuwei Commandery and the Chief Commander of Zhangye, and the owner of four titles of Generals.

Bronze Light Chariot

Length 95.5-109 cm, height 22-26 cm, thickness 14.3-13.5 cm

Eastern Han dynasty (25-220CE)

Unearthed at Leitai Tom, Wuwei City, Gansu Province

Gansu Provincial Museum

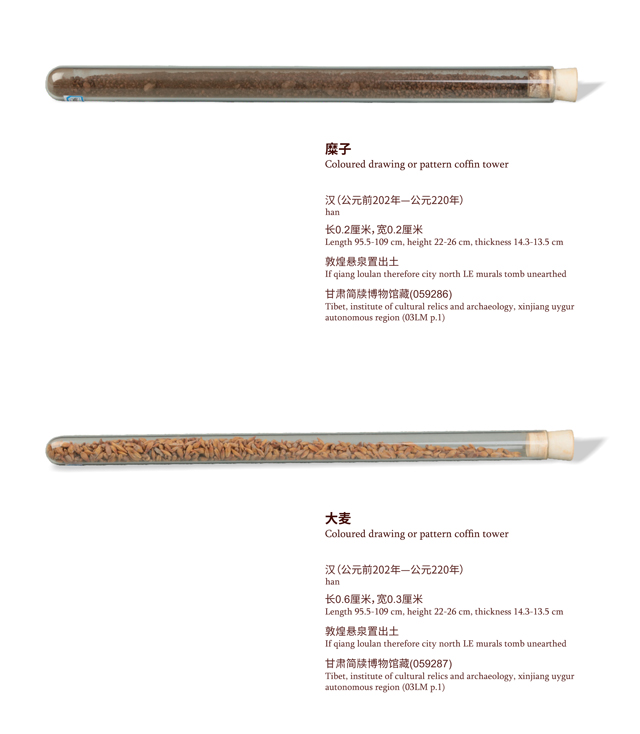

5. Aristocrats in Loulan

Loulan was located at the Lop Nur area on the east edge of Tarim Basin. In the 2nd century BCE, the Western Han armies counterattacked Xiongnu and opened up the Silk Road. Since then, Loulan became a significant place on politics, military, and economics, as well as the transportation hub that linked inland China and the Western Regions. People that gathered here included not only the Han Chinese from inland, but also visitors from the empires of Kushan, Parthian, Dayuan, and the Kangju Sogdians. Among them there were emissaries, soldiers, merchants, monks, and immigrants. After a long and exhausting journey in the desert, people stopped here to take a rest, handle official affairs, trade commodity, preach and teach Buddhist dharma, recruit provisions, and then continued their journey to a remote destination. In the interaction with the outside world, the life of Loulan people had quietly changed. Among the Loulan people with higher status, the gorgeous Han-Chinese-style silk robe with cross collar replaced the traditional loose-fitting woolen pullover; the ordinary cotton cloth also imitated Han-Chinese-style outfit to be edged with color silk. In addition to silk clothing, lacquerware and bronze mirrors from Central Plains, and glass beads from the West, also became Loulan commoners’ favored appliances and accessories. On the mud wall in big courtyard houses, the exotic wall tapestry with lion motif was hung. Besides the earthen stove bed, there were carved wooden chairs from ancient Persia that allow people to sit with legs pendant. Chopsticks from Central Plains were added to daily utensils, and clay cauldron steamers were used for steaming and boiling.

Color-painted coffin board

Jin Dynasty (3rd–4th centuries CE)

Length 207 cm, width 57 cm

Unearthed at the LE mural tomb, ancient Loulan City,Ruoqiang County

Institute of Cultural Relics and Archeology in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region

Jin Dynasty (3rd–4th centuries CE)

Short sleeve damask robe

Length 88 cm, remaining width (cuff to cuff) 64 cm

Unearthed at the LE mural tomb, ancient Loulan City,Ruoqiang County

Institute of Cultural Relics and Archeology in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region

Lacquered vanity box

Jin Dynasty (3rd–4th centuries CE)

Full height 5.6 cm, base diameter 8.8 cm

If qiang loulan therefore city north LE murals tomb unearthed

Institute of Cultural Relics and Archeology in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region

String of glass beads

han

Bead's diameter 0.25-1.8 cm

Unearthed at Loulan site, Ruoqiang County

Institute of Cultural Relics and Archeology in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region

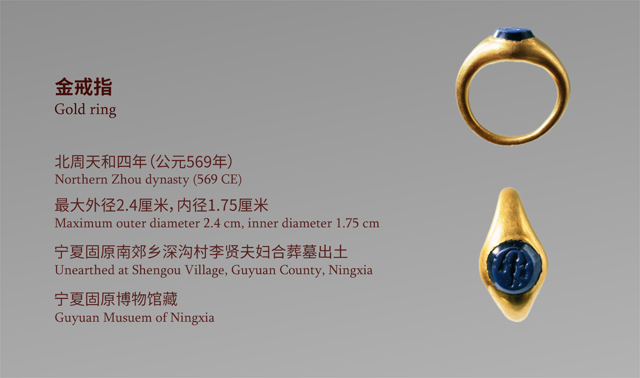

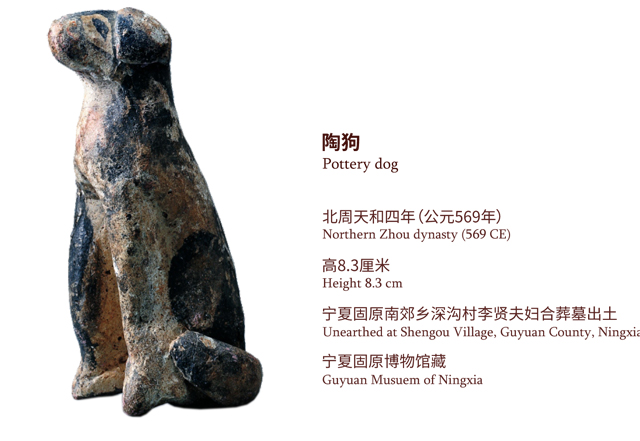

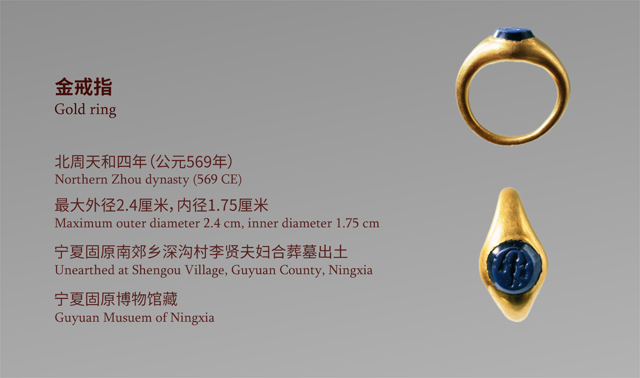

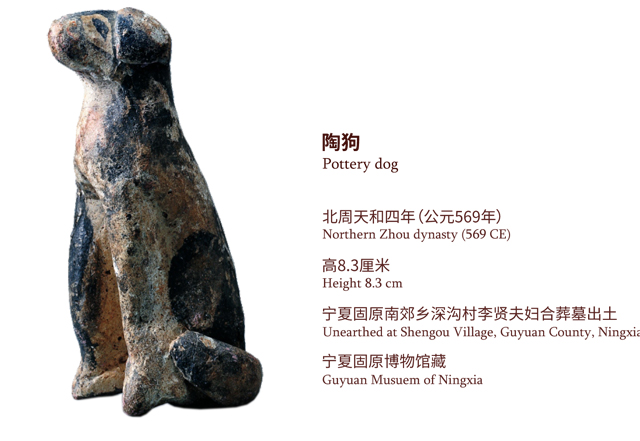

6. The General-in-Chief in Guyuan County

In the southern suburb of Guyuan County, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, there is a plateau. In the fall of 1983, archaeologists found a husband-and-wife joint tomb, thus the dust-laden history of Li Xian, who was a prominent general with illustrious family history and a loyal follower of the Yuwen family was brought vividly to life.

Li Xian, courtesy name Xianhe, was from Gaoping County, Yuanzhou Region. Li Xian’s ancestors were from Chengji County, Longxi Commandery (present-day Tianshui City, Gansu Province). Based on Li Xian’s epitaph, many scholars believe that Li Xian was from the Tuoba clan of the Xianbei, a pastoral people from China’s northern frontier. From his grandfather, who had been a guard of Gaoping County, three generations of the Li family worked as local officials in Yuanzhou Region. Li Xian followed the Xianbei general Yuwen Tai’s army and was appointed Supreme General of the Pacification Army, and Commander-in-chief. In the second year of the Datong reign period of the Western Wei dynasty (536 CE), Li Xian quashed Doululang’s rebellion in Yuanzhou, and was promoted to Regional Inspector of Yuanzhou, overseeing military and administrative affairs. After several years of hard work by Li Xian, Yuanzhou Region gradually became the base of the Yuwen family, who supported the Western Wei dynasty until they established the Northern Zhou. In the third month of the fourth year of the Tianhe reign period (569 CE), Li Xian died in Chang’an City, at the age of 66. His coffin was transported back to Yuanzhou, where he was jointly buried with his wife at Shengou Village, Xijiao Township, Guyuan County.

Armored rider figurine

Northern Zhou dynasty (569 CE)

Length 17.6 cm, full height 17.5 cm

Unearthed at Shengou Village, Guyuan County, Ningxia

Guyuan Musuem of Ningxia

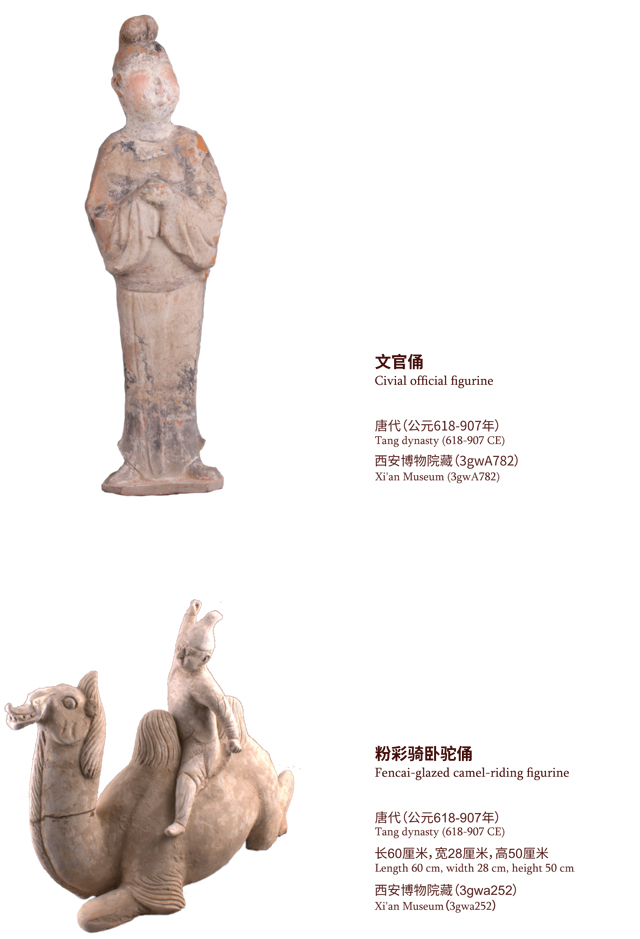

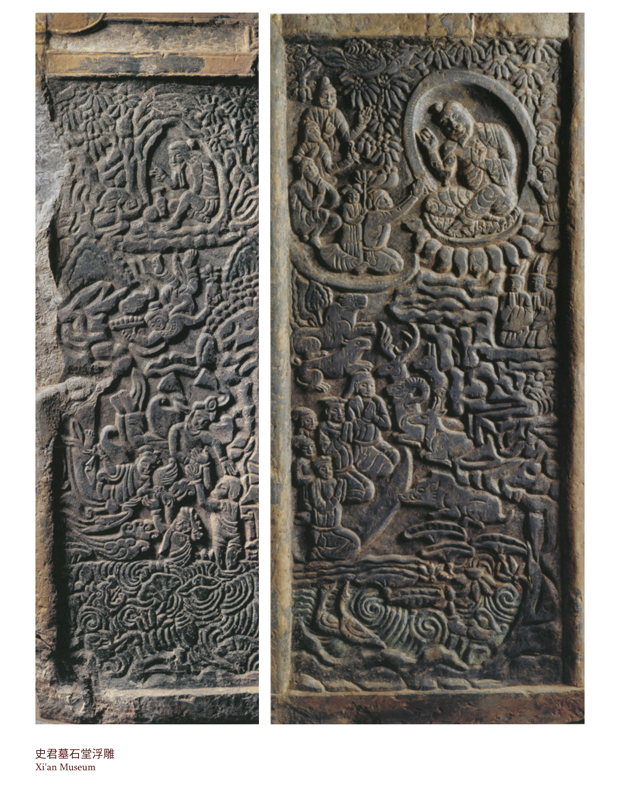

7. The Western Merchant along the Silk Road

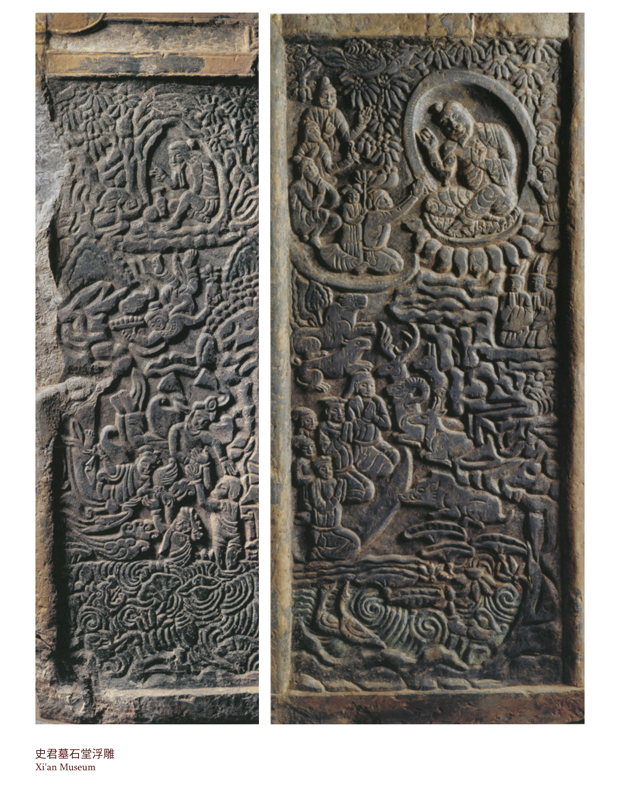

In the first month of the second year of the Daxiang reign period (580 CE), a funeral of Master Shi and his wife was held in the east of Chang’an City. Master Shi was a sabao [caravan leader] in Liangzhou Region. Their three sons buried them in Longshouyuan according to their wishes.

Master Shi (493-579 CE), or Wirkak in Sogdian, was from the State of Shi. His grandfather, Ashipantuo, had been a sabao in his native land. His father was Anujia. The State of Shi (Kess) was an ancient state in the Western Regions which was one of the nine tribes of Zhaowu. The seat of the State of Shi was at Kesh, located in the basin between the current Amu River and the Syr River, i.e. the Sogdian region in classical literature. In the second year of the Shengui reign period of the Northern Wei dynasty (519 CE), Master Shi married Wiyusī, née Kang, at Xiping (present-day Xining City, Qinghai Province), and had three sons. After starting a family, Master Shi, like his ancestors, traveled back and forth on the ancient Silk Road with his own caravan. At some point, probably during the Western Wei dynasty, Master Shi’s whole family moved from Xiping to Liangzhou and he was appointed as Chief of the Judicial Department of the Sabao Bureau. Then he was made sabao of the Liangzhou Region in the Northern Zhou dynasty, and then moved to Chang’an City. He died in 579 CE at the age of 86. His wife, née Kang died a month later.

Length 2.4 m, width 0.71-0.97 m, height 0.82-1.2 m

Stone sarcophagus of Master Shi (replica)

Northern Zhou dynasty (580 CE)

Unearthed at the tomb of Master Shi,Xi'an City, Shaanxi Province

Xi'an Museum

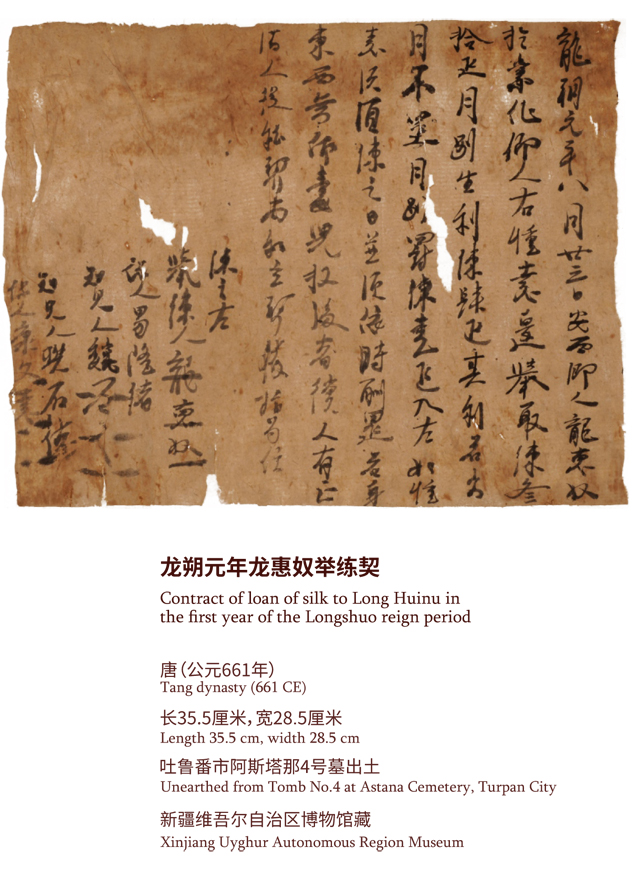

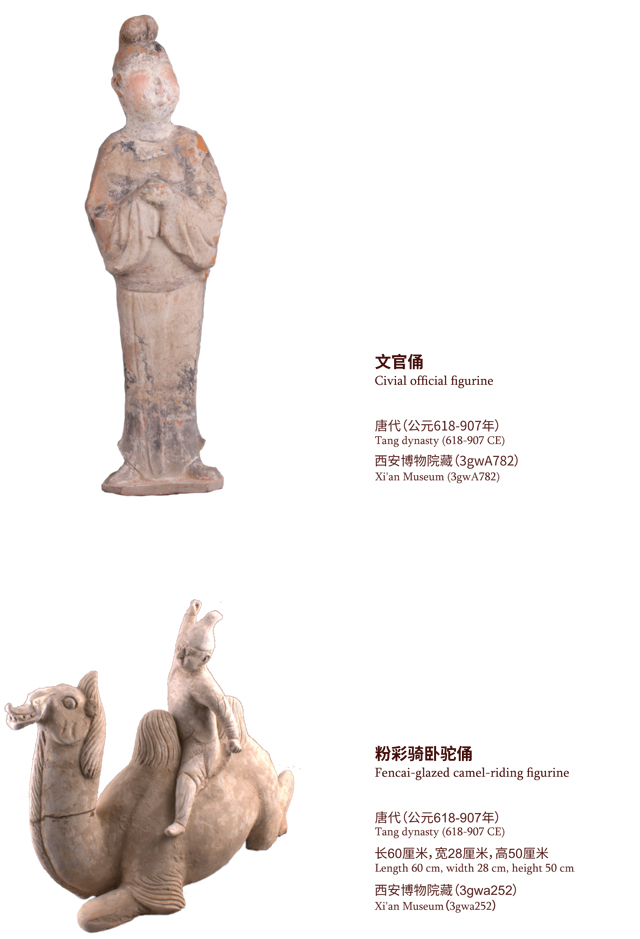

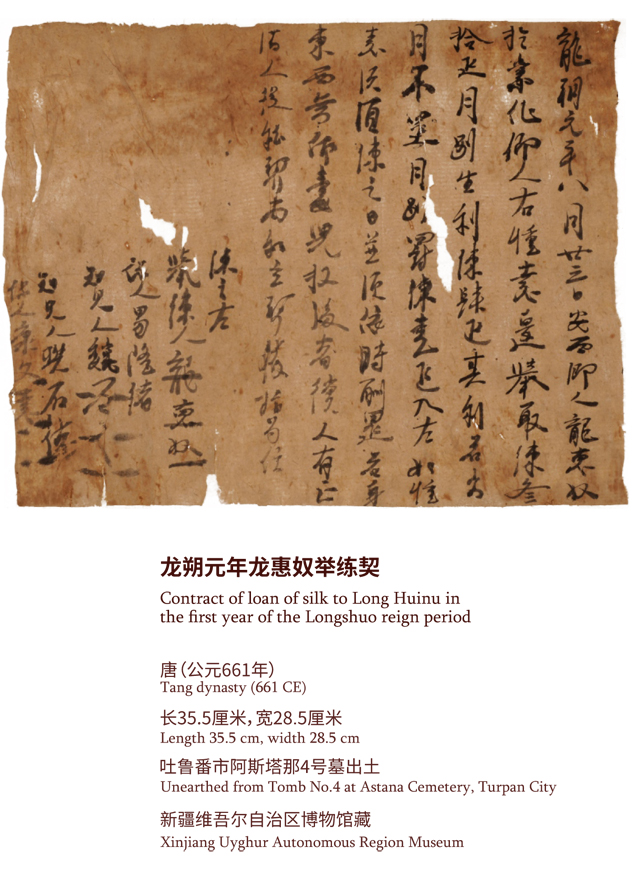

8. The Moneylender in Xizhou Prefecture

In the fourteenth year of the Zhenguan reign period (640 CE), the Tang dynasty unified the Western Regions after the fall of the Qu Kingdom of Gaochang. After the third year of the Xianqing reign period (658 CE), the Tang dynasty set up the Protectorate of the Pacified West that extended its military strength to the Western Regions. Zuo Chongxi lived in the area of the Chonghua Township, Gaochang County, a multi-ethnic township located in the northern part of Gaochang County. He became very rich with his financial management skill when he was just at the age of 40s.

Not only a private money lender, but Zuo was also a guard of the local Qianting Assault-resisting Garrison, in other words, a wealthy garrison soldier. In addition to self-support, he also lent money to others for battle preparation. His military success earned him “distinguished serviceman” of the Xizhou Prefecture. The flourishing development of the garden production at that time helped Zuo gain profits through the merger of vegetable gardens and became a virtuous rural elite that willing to help others. Zuo Chongxi converted to Buddhism in his early age. He built statues of a Buddha and two Bodhisattva ten years before his death. He read the Ullambana Sutra frequently and donated money to monks. The epitaph, account books, and contract documents from Zuo’s tomb recorded his legendary life.

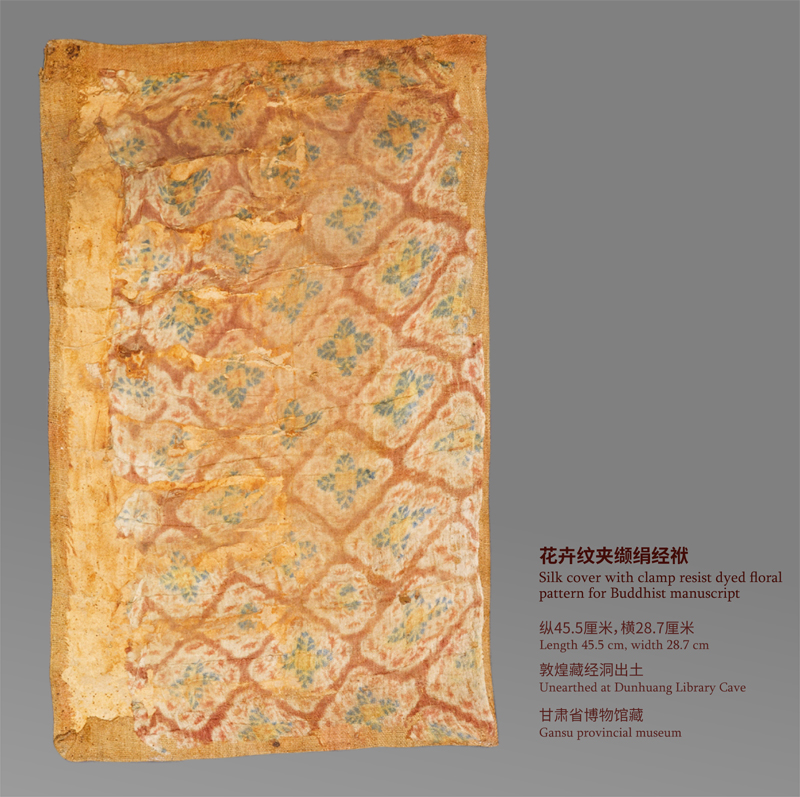

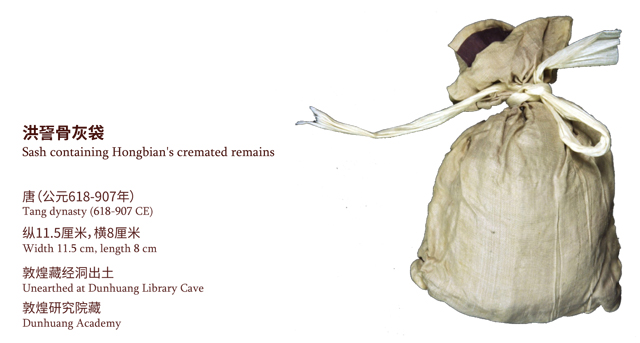

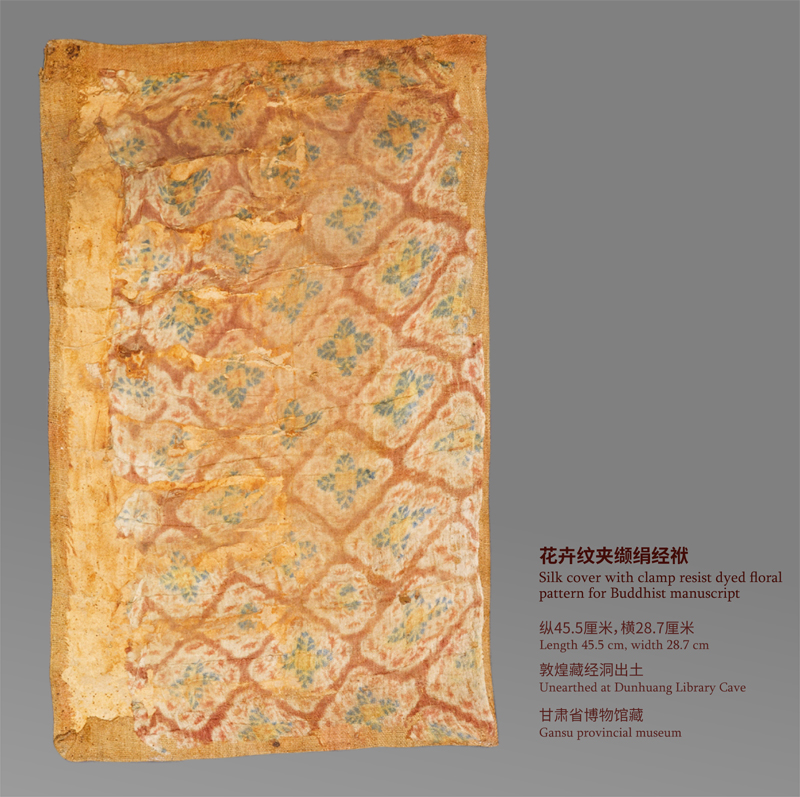

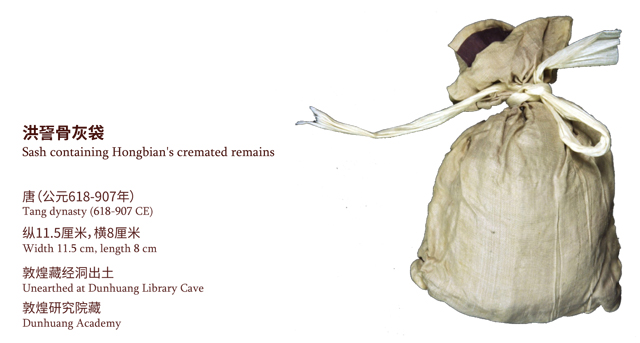

9. Buddhists in Dunhuang

Mogao Cave 17, also known as the Library Cave, is located on the north side of the entrance corridor to Cave 16. Built during the fifth year of Dazhong reign and the third year of Xiantong reign of the Tang dynasty (851-862), it was the shrine that housed the statue of Hong Bian, the Buddhist Controller-in-Chief of Hexi region in late Tang period. Having become a Buddhist monk since childhood, Hong Bian was a pupil to Moheyan, the most famous Chan Buddhist master during the reign of Trisong Detsen of the Tibetan Empire. With endless study and hard work, he became an eminent monk of his generation and was regarded as a master both by priests and laymen. In 821 CE, he was appointed by the Tibetan ruler as the Supervisor of Laws and Vice Instructor in Buddhism, and thus became one of the top-ranking monks in Dunhuang. In 832 CE, he was appointed again by the Tibetan ruler as the Chief Instructor of Buddhism, which was the leading role of Buddhist monks in Dunhuang. Although greatly appreciated by Tibetan rulers, Hong Bian did not forget his ancestor’s unfulfilled wish. In the second year of Dazhong reign of the Tang dynasty (848), Zhang Yichao led an armed rebellion against the Tibetans, in which Hong Bian also took part as the leader of Dunhuang monks. Taking his influence among Buddhists as an advantage, he organized armed monks to join the rebellion army. After the military government of Guiyi Army was established, Hong Bian continued his management of Buddhist affairs in Dunhuang as the leader of Buddhism in Hexi region. In the third year of Xiantong reign of Emperor Ruizong of the Tang dynasty (862), Hong Bian died in Dunhuang. After his death, his followers or family renovated the granary of the monastery into a cave shrine for Hong Bian.

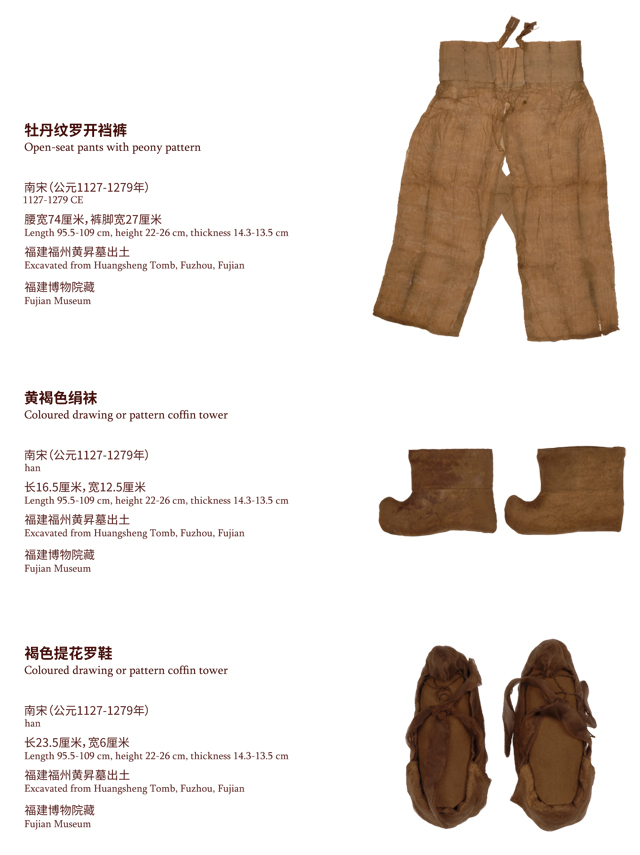

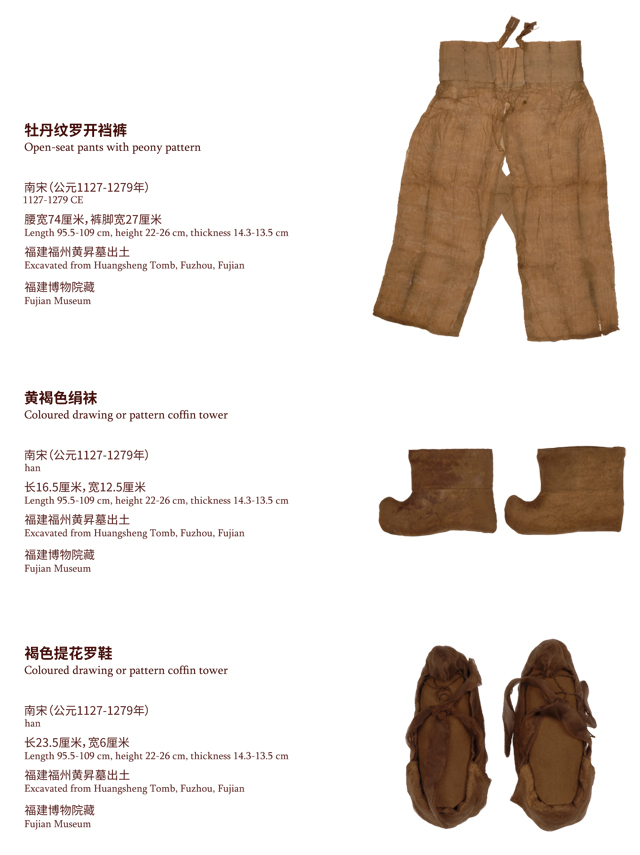

10. The Daughter of Customs Chief

In October, a large number of funerary objects were unearthed in the tomb of the Fucang Mountain located in the north of Fuzhou City. The owner was Huang Sheng, a noble woman with the royal family of the Southern Song Dynasty. In particular, a myriad of exquisite silk garments and accessories attracted people’s eyes, which unveiled the extravagant life the noble women lived at that time.

The relatives of Huang Sheng were meritorious government officials, for which, she was entitled to these fancy funeral items. According to the inscription on the gravestone, Huang Piao, Huang Sheng’s father, was the Zhuang Yuan (Number One Scholar, conferred on the one who comes out first in the highest imperial examination) in 1229. During the Ruiping period (1234-1236), he was governor of Quanzhou and concurrently director of Bureau of Foreign Shipping Affairs in charge of the general affairs and foreign trade in that city. Huang Sheng’s husband was Zhao Yujun, magistrate of Lian Cheng County. His grandfather was Zhao Shishu, the ninth descendant of Zhao Kuangyin, the first emperor of the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). Huang Sheng was married to him at the age of 16, which honored her as a noblewoman in the royal family, but unfortunately, she passed away at the age of 17. The wear and other silk products were well preserved, which just represent a miniature reflecting the booming of the silk industry of Fujian Province in the Southern Song Dynasty and its influence on the Silk Road.

11.People on Nanhai No. 1

The Nanhai No. 1 Shipwreck, found in the waters between Taishan and Yangjiang Tcounties in Guangdong Province, is an important site on the Maritime Silk Road. The excavated ship has a V-shaped body composed of the keel and multiple shipboards. Its short and fat body allows for a high degree of safety, buoyancy and resilience, and the capacity to carry a large cargo. A rich variety of artifacts have been recovered from the Nanhai No. 1, particularly porcelain, iron and bronze ware, but also gold, silver, cinnabar/mercury, and the remains of different species of plants and animals. There are also many ornamental pieces made of precious metal, and objects of daily use. Traces of silk fabric can be seen on these objects.

At the same time, Nanhai No. 1 offers us a vivid example of the maritime activities Aof people of ancient times. There were not only the captain and crew on board but also guests traveling between different countries on the Maritime Silk Road. The remains of dozens of species of plants and animals have been recovered from the ship, and there are even handcrafted objects made of fish bones, revealing both the hardship and fun experienced by the crew in their lives at sea.

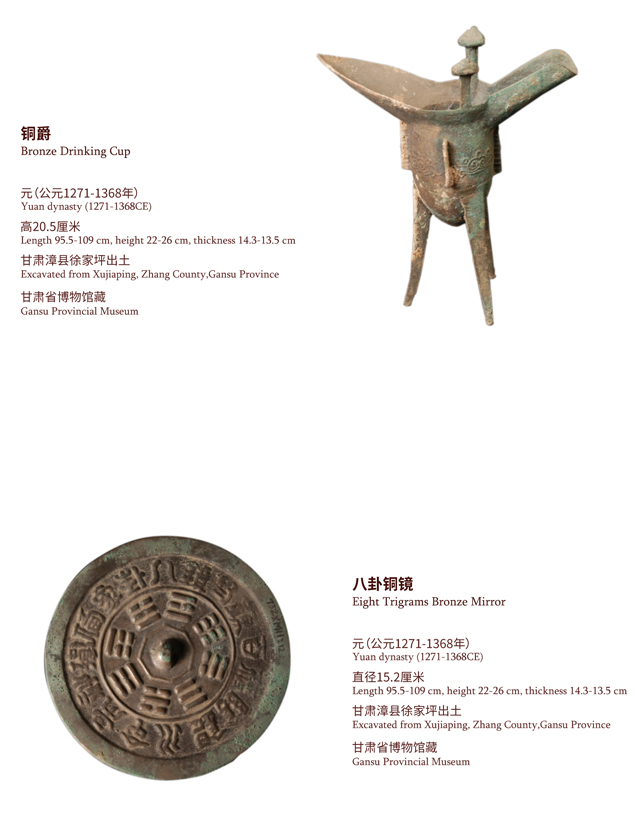

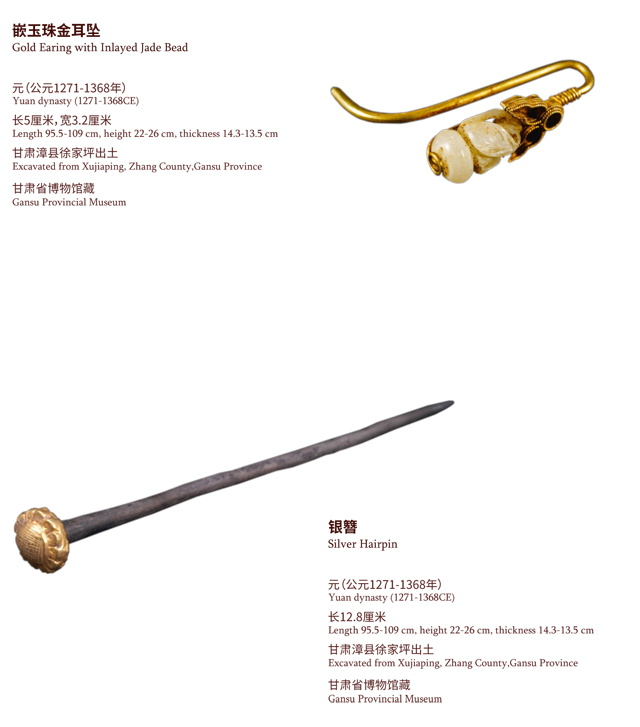

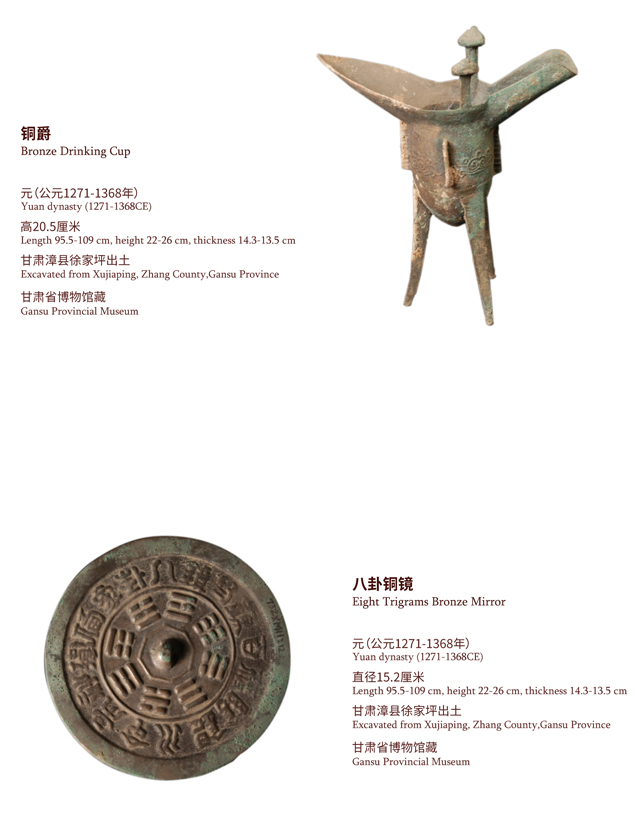

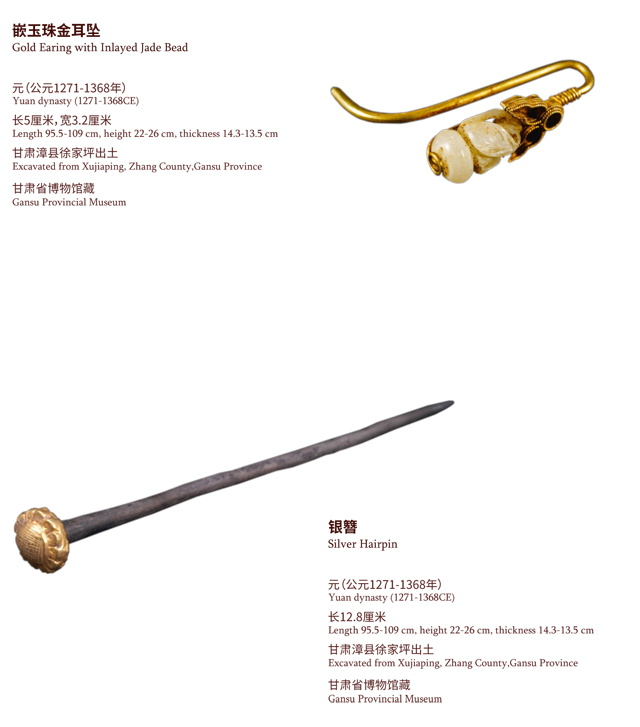

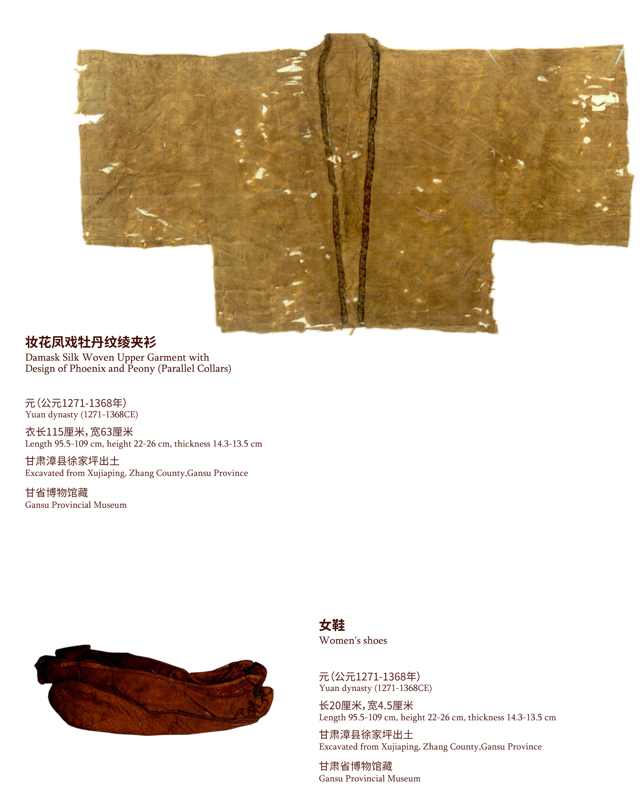

12.Warriors of the Steppe

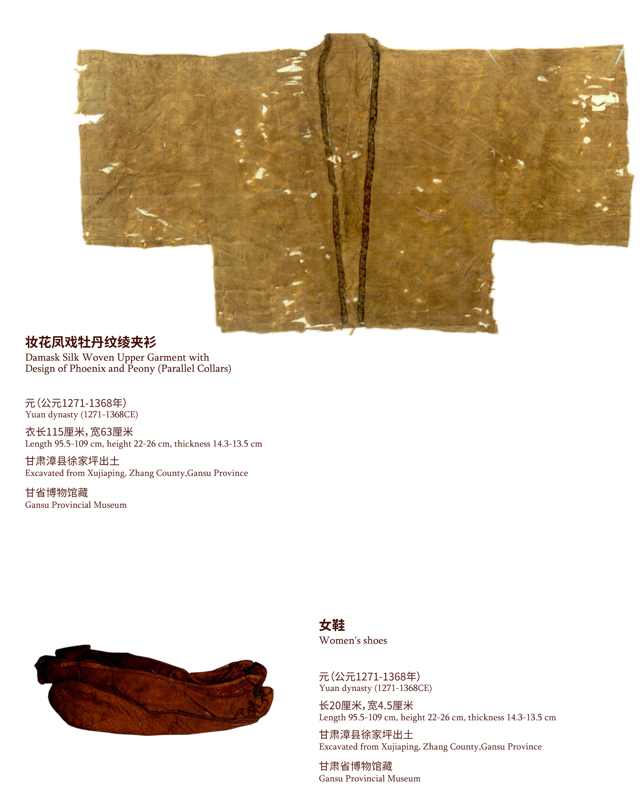

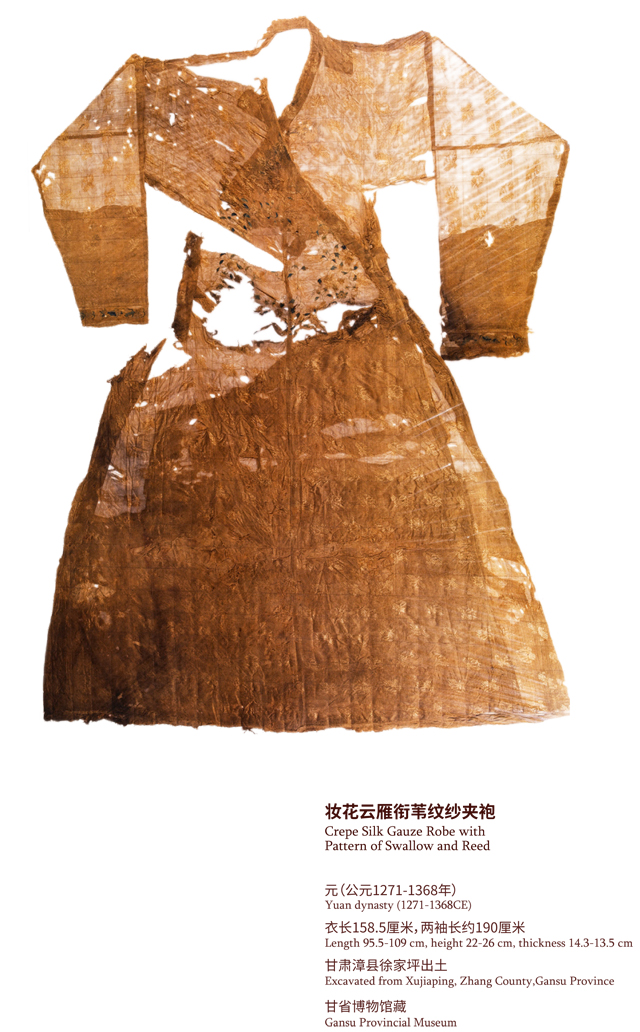

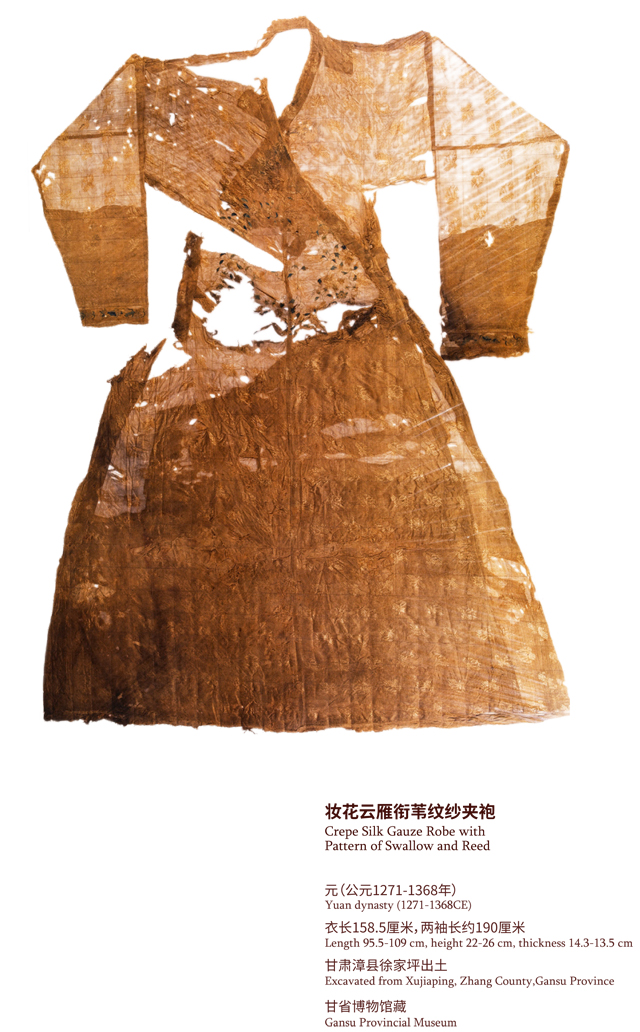

The Wang Family Cemetery is located on the east slope of Xujiaping Village, 2 kilometers southeast of the county seat of Zhangxian, Gansu Province. It is one of the most concentrated and complete family cemeteries of the Yuan dynasty, and another seven tombs of the Ming dynasty were also found.

Wang Shixian, courtesy name Zhongming, was born in Yanchuan (modern-day Yanchuan Town, Zhangxian County) of Gongchang (modern-day Longxi County, Gansu Province). During the period of the long-lasting wars between the Jin and the Western Xia, Mongols, Southern Song, Wang Shixian took the opportunity to gain his military experience and to expand his strength. In the second year of the Zhenyou reign period of the Jin dynasty (1214 CE), Wang Shixian was promoted to Chiliarch, then was further advanced to Battalion commander, then the Controller of Gong Prefecture, the Vice Prefect of Pingliang Superior Prefecture, the Defense Commissioner of Longzhou Prefecture, and finally the Chief Commander of Gongchang Route after he took control of Gongchang in the third year of the Tianxing reign period (1234 CE). Later, he surrendered to the Mongols by offering more than twenty prefectures under his control, including Qin and Gong, and remained in his original official position. In the year of 1240 CE, he was given a golden tiger commander’s seal because of his military success in the Shu region, and was granted the privilege of the Chief Brigade controlling local military and civil affairs, which made him among the Han ethnicity nobles of the Yuan government. In the same year, Wang Shixian died of illness, and his second son, Wang Dechen inherited his noble title. In the subsequent war of conquering the Shu region, Wang Dechen died in battle, and the Wang family army was then led by his elder brother Wang Zhongchen and his younger brother Wang Liangchen, together with his son Wang Weizheng.

In terms of the ethnicity of the Wang family, there are different viewpoints in the academic society, including three major types: the Onggud tribe of the Mongols, the Han, or the Tubo. Each of the opinions is supported by evidence. Therefore, the research on this issue is still in progress.

13. The General in Yanchi County

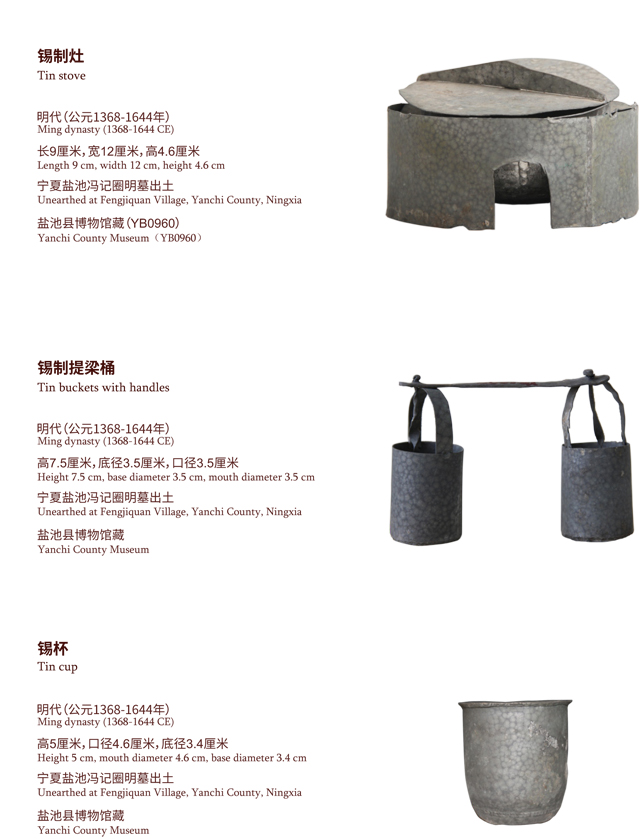

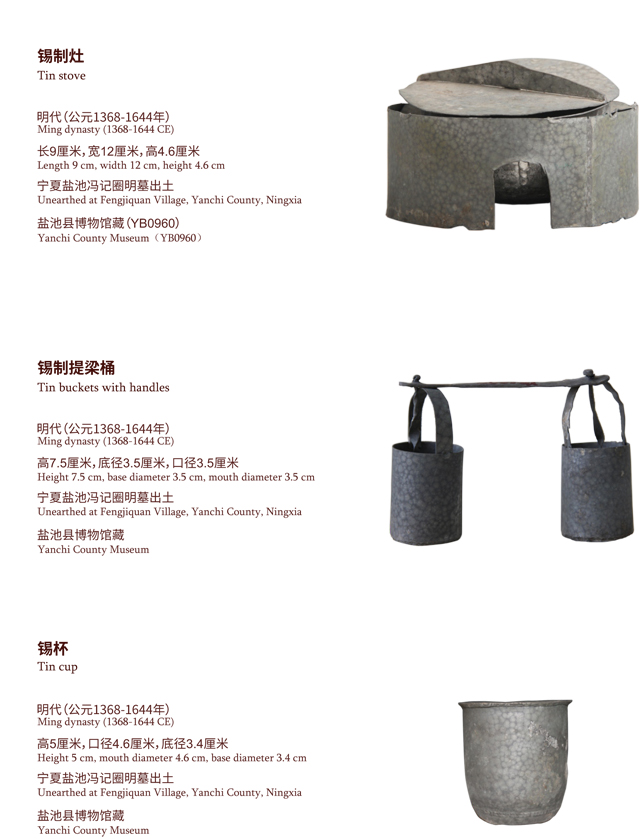

On July 18, 1999, torrential rain exposed three underground brick tombs of the Ming dynasty in a desolate sand-plain out of Fengjiquan Village of Huamachi Town, Yanchi County, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. The occupant of Tomb M2 was Yang Zhao (1488-1544), whose courtesy name was Zhongqi and sobriquet title was Hongshan. Yang Zhao’s ancestors were originally from Taizi Superior Prefecture of Liaodong Peninsula and bore no surname. At the end of the Yuan dynasty, Yang Zhao’s great-great-grandfather Shudai took the opportunity to submit to the authority of the Ming dynasty and received the title Vice Commander of the Right Imperial Insignia Guard. Yang Zhao’s great-grandfather, Mahuerke, was a loyal follower of Zhu Di and was given the surname Yang. Yang Zhao’s father, Yang Ying, was transferred to Ningxia to resist the invasions of Tatars and Oirats. From then on, his descendants served as loyal rear guards in the Ningxia military garrison. Yang Zhao was only three years old when he came to Ningxia with his parents. When he grew up, he inherited his father’s military duties. In the thirteenth year of the Jiajing reign period (1534), for successfully defeating the Tatar jinong, he was promoted to Commander, then Commander-in-chief, and even as high as General of Exemplary Fortitude.

Arguably, the Yang family was a microcosm of the Mongols who chose to submit and could be loyal to the Ming dynasty. There were many Mongols who served as officers in the Ming dynasty. Several generations of marriages determined by geo-politics accelerated the assimilation and ethnic integration of the foreign peoples who submitted to the Ming.

Round-collared robe with gold qilin patterns and miscellaneous treasures and clouds

Ming dynasty (1368-1644 CE)

Length 128.5 cm, width 175 cm (across arms), hem width 147.5 cm

Unearthed at Fengjiquan Village, Yanchi County, Ningxia

Yanchi County Museum(YB1264)

Pay attention to us

×

Pay attention to us

×